Djali Brown-Cepeda — a filmmaker, archivist and native New Yorker — created a digital photographic archive of New York City’s Latinx and Caribbean history, Nuevayorkinos, to affirm her roots and allow others to affirm theirs. Equal parts extended family album, urban chronicle and vernacular yearbook, Nuevayorkinos feeds on image submissions. They range widely: the oldest dates from the 40s, and the most contemporary is from the early 00s. The archive is a locus of storytelling in image and bilingual text: delivering In Living Color, “Fly Girl” vibes, sweet birthday remembrances, homages to beloved locations like the East River Park Bandshell/Amphitheater, plus anecdotes about dads who show up and heartbreaking queer struggle.

Djali considers storytelling to be a vehicle for decolonization, and a way of valorizing communal ties to New York City, especially as the cost of living and gentrification steadily denature the cityscape for those who have been in the boroughs for generations. Coming off Nuevayorkinos’ participation in the fifth edition of the Latin American Foto Festival at the Bronx Documentary Center, we spoke with Djali about celebrating lineage, creating strong visibility and documentation as a form of love.

What was your own household’s relationship to family photos and archives before you started this project?

I was always interested in my parents’ and grandparents’ photo albums, because there aren’t many of my childhood. I think there are maybe three or four albums, most of which end around age 10. While there are some digital photos, nothing compares to holding and flipping through a photo album. A few years ago, I began digitizing my family archives, starting with my maternal grandparents’ treasure trove of photos: my mother’s childhood in the Dominican Republic, scenes from my grandparents’ respective lives, before and after they met one another, coming to the U.S. I started scanning my dad’s collections, too. I’m most excited about getting into my paternal grandmother’s photos, as she was a photographer in her 20s.

Who are your favorite photographers — of New York? Of the Latinx community? And more widely?

There are so many photographers whose work has inspired me and continues to. Some of my favorite New York City photographers that have documented our cultures are Jamel Shabazz, Henry Chalfant, Joseph Rodriguez, Joe Conzo Jr., Diane Arbus, Helen Levitt, Nan Goldin, and Bruce Davidson. Other photographers whose work I gravitate to are Gordon Parks, of course, James Van der Zee, Joan E. Biren, Stefan Ruiz, Rahim Fortune, Juan Brenner…

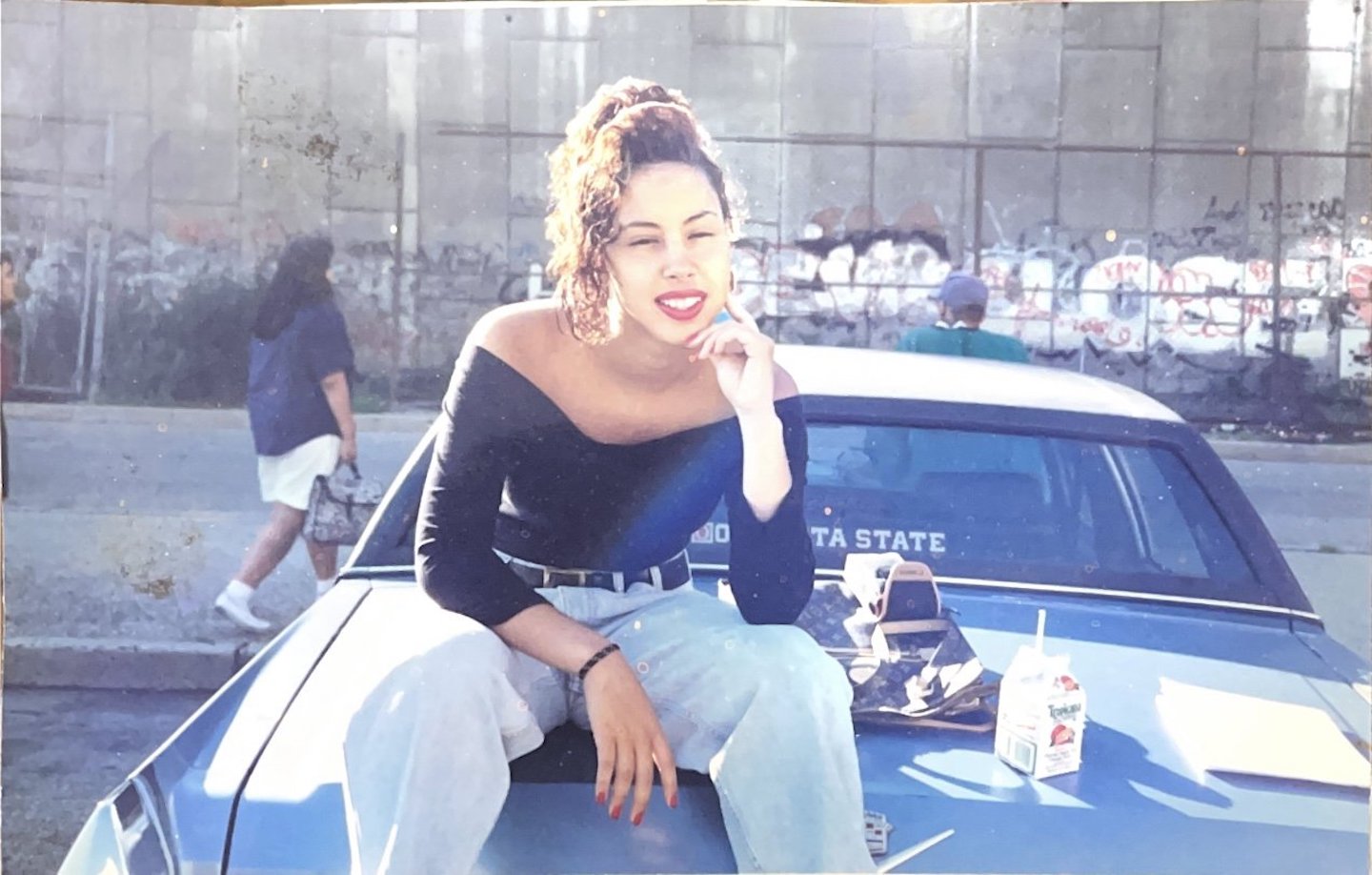

The first photo posted on Insta was of your mom. Can you talk about this photo and how it set the tone for the project?

It made sense to start with her for a few reasons. Most obvious, I could easily access her photos and talk to her about what that photo and time meant for her. But aside from that, my mother’s story is one that’s shared across this city, and country: first-generation New Yorker, born here, raised in Dominican Republic, then came back here, went through moments where she didn’t feel “x” or “y” enough as someone — ni de aquí, ni de allá (neither here nor there). A story filled with overcoming obstacles and adversities, but also love and strength. She had a lot to navigate in this strange place called the United States, but, over time, found her people, her community — other Dominiyorkers trying to figure it all out.

In crowdsourcing submissions, do you see certain trends or patterns? Is there a socio-anthropological bent that has resulted from this endeavor?

As first, second, third-generation immigrant communities, there are similar thematics that arise: migration, adapting to life en la gran manzana (in the Big Apple), navigating society’s expectations, the battle against (or adoption of) assimilation, seeing snow for the first time. But what connects all of these stories is that they’re all centered in love: love for one’s family, one’s friends, and one’s community. The anthropological lens that’s risen from this is a byproduct of the work naturally, since there’s more to learn about the city and our respective communities through each of these stories. But it’s anthropology that leads with and exists because of said love. The history of anthropology, like the majority of the sciences, is rooted in Othering, Orientalism, racism and xenophobia. Nuevayorkinos — a project made for the people and thriving because of the people — is antithetical to that. We document and preserve not from the Ivory Tower, but from the block.

Using visuals as a conduit to representation and activism: in what ways is this galvanizing — and in what ways is this limited — to facilitating change?

Throughout history, visual media has always been a useful tool to help catalyze change. Nuevayorkinos was created, first and foremost, out of a necessity to plant our proverbial flag as Black, Latino, Immigrant ÑYC. Especially as our neighborhoods are being increasingly gentrified. Our mom-and-pop shops are closing, our blocks are losing their accents, we’re being displaced. That’s one of the functions of the geotags: on one hand, it’s a way to center our stories in neighborhoods that many wouldn’t associate us with, like Williamsburg. On the other hand, it’s a way of showing viewers our deep roots in this city. Nuevayorkinos also seeks to facilitate change by showcasing a range of different photos from different backgrounds and boroughs to show that while we’re similar and have shared histories, we also have our differences. Like Blackness, Latinidad is not monolithic. Nuevayorkinos is here to combat the single-story, one-note narrative associated with our people.

This is a localized project: there are glimpses of bright orange subway seats, the Manhattan horizon and the Circle Line, amongst other urban specificities. What does New York as a place symbolize to this project?

New York is everything. She’s a character in herself. New York City has always been a symbol of hope and opportunity for so many. New York is the place where you can quite literally land with $1 and a bag of clothes, then find the opportunity to open your own business. It’s a place that embodies inspiration, esperanza. It’s finding home everywhere, from your vecinos (neighbors) to an older woman calling you mija (darling). Home can be found on the futbol fields of Flushing Meadows, on the dancefloors at bars on Roosevelt Avenue, in the smiles of the homies at skate parks when they finally land that trick they’d been trying 1,001 times. Home is being unphased by Showtime performers, knowing they’re masters of their craft and won’t kick you when flipping on the subway poles. Home is being able to sleep through the cacophony of sounds happening outside your window. Home is hearing how hype New Yorkers get when hearing “yerrrrrr!”.

Do different boroughs seem to highlight different experiences or communities?

There aren’t many thematic differences necessarily that stand out per neighborhood; it’s all pretty related across the board. But different neighborhoods and boroughs have different diasporic strongholds. For instance, most of our South American and Central American submissions come from Queens, as that’s historically been a stronghold of those diasporas. Most of the submissions from Washington Heights, Upper Manhattan and Harlem, come from Dominican and Puerto Rican communities, since those are historic Caribbean enclaves.

The cultural conversation around the need for diversity and representation is becoming louder and more prominent — do you feel a social shift?

There are definitely more spaces being created by Black and Indigenous Latino and Caribbean communities for us, and that’s amazing. We get consumed with trying to do all that we can to be invited to sit at someone else’s table. Too often, we’re excluded. I’m happy to see that folks are making their own.

The images are offset with reminiscences. Is there anything that felt especially impactful to receive? Or anything truly unexpected?

It’s a powerful thing: penning your own story. We don’t edit what people write: everyone presents the truest version of themselves. Three years down the line, it’s still exciting receiving new submissions. People have reconnected with long-lost friends through this project, have reunited with family, have worked through adversity and have further found community. Writing can be cathartic, it’s therapeutic.

Showing at the Bronx Documentary Center, did you take on a curatorial role? How do you make an image selection?

Yes, I curate the page as I curate the shows. My partner in life and love Ricardo Castañeda — the Creative Director of Nuevayorkinos — and I usually co-curate the physical shows. As a graphic designer, his eye catches things that I wouldn’t necessarily think of, like placement of different frames next to one another and the position of certain images themselves. The photos from the Bronx Documentary Center show were received via Open Call submission. Bronxites had roughly a month to send in their photos, videos and stories. From there, the submissions were sent to the BDC team. Between the team, myself and Ricardo, we narrowed it down to the handful that you see on the physical banners on E. 150th Street and Melrose Avenue, along the gates of the Church of the Immaculate Conception. Since we received nearly 100 images, we wanted to showcase all of them, and not a select few. Because all stories matter. So, we chose to extend the show virtually and have it live permanently on the Nuevayorkinos website.

How does showing the images in physical space change them, or animate them differently, relative to digital?

Online is great because there’s a wider reach. But there’s so much that’s lost in a technological world. Exhibiting the archival work in a physical space allows us to really create an enveloping space for all viewers, transporting them to their family’s kitchen or abuela’s living room through the frames we use and the installations we usually build that go with whatever show we’re working on. It’s also such a rewarding and humbling feeling to see people physically interact with the work: smiling, taking photos of and posing with whatever photo resonates with them.

The old-school fashions and previous topographies of New York are so endearing and special — it’s wonderful to see the different “eras” depicted in details big and small. Is there a celebration of nostalgia in this project too, as much as a sense of re-defining the record or narrative history?

Old school New York, her barrios and her characters need to be protected at all costs. While we single-handedly will never stop capitalism and gentrification, we combat it in the way that we can: by making ourselves, our lives, our stories, our communities and our peoples visible.

It’s not about redefining the narrative because everyone knows that New York City has always been a refuge for immigrants, and continues to thrive because of our communities. Yet, Black, Brown, immigrant, diasporic New York is taken for granted. Our people deserve the world because we give all of ourselves to keep this city, and country, afloat.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on social media and mental health.