Mary McCartney‘s “A Moment of Affection” (running June 27 to September 4) is a new photographic exhibition winnowed from her multi-decade archive. On view in a barn-turned-gallery space at Château La Coste in Provence (made in curatorial collaboration with Georgina Cohen), the thematic distillation considers what it means to be tied to others, both within one’s intimate circle and in the surrounding world.

While members of Mary’s family have been photographed unceasingly — she’s the daughter of musician Paul McCartney and photographer Linda McCartney, and the older sister of designer Stella McCartney — her gaze tempers these famous figures from capital-I Icons to simply close kin. Mary looks beyond them just as appreciably, finding glimpses of tender-hearted synchronicity without veering into sentimentality.

We spoke with the photographer to discuss portraits without faces, getting to grips with showcasing family, and widening the scope of what qualifies as affection.

How did you make your selection for this project?

I came up with the title first. The way that I take photographs is: I collect them and archive them away. And then, when I’m asked to do an exhibition, I search for a theme. The challenge is whether a picture fits the theme of the exhibition. That’s the way that I like to work — knowing that it’s going to become something in the future. For this, I went through every single contact sheet.

It’s interesting that you create connections afterwards.

It’s a range, rather than a study. I thought: what is the essence of what captures that moment? Affection is a basic human instinct. But even the one image of two trees hugging…

…I love that one!

For me, that was the key image. Because I was like, Well, look, it doesn’t have to be two people. It’s nature! It has a lot of emotion. I’m glad to hear that you really liked that one. I didn’t want to be too predictable.

It’s so charming to think of the natural elements interacting in an embodied way.

It’s like a real hug! It really looks like they’re embracing each other. It was taken while wandering — I feel like maybe I’d even walked past those trees before? You know, if you’re in a certain mood, on a certain day, and you’re observing… suddenly that kind of moment has so much more meaning. That’s the biggest piece in the show. It’s like, six foot tall, six foot wide.

On Instagram, you’ve been tagging #momentofaffection for a long time now.

Yes, it started in the pandemic. I’d see something that felt almost like a throwaway moment… a moment of affection could be just standing next to each other, or holding someone’s hand.

There’s a mix of lived-in moments with family and furtive glimpses of strangers. Does your own intimacy with — or distance from — the subject affect how you photograph?

Whether with family or friends, or on a commission, or wandering around, it’s a similar feeling, a similar brief. There’s an intimacy in being invited into people’s personal space — whether it’s my family, or someone else’s family. In a weird way, my family is more difficult for an exhibition, because I look at them like snapshots or an album. I take them, archive them, then look at them again with a bit of perspective. Like “Mother and Sister” is a very personal picture to me; it feels kind of Madonna and Child… my mum kissing her head, the way she’s holding her, and even the veins on her hands. I think it will resonate with other people. I can imagine someone else connecting in a way that will be personal to them.

Does having family members who are much-photographed and in the public eye create a visual challenge, because there’s a lot of existing representation?

Like, is it more challenging to take a family photograph? Yeah. And I question myself more before putting a family photograph out there. When I started out, I wouldn’t allow myself to use many family photos; now I look at it differently. They’re part of experiences I’ve gone through, the things that give me my creativity. Before, I’d be like, “they’re family… and this is my photography”. I’d keep it separate. Now, I mix. There were two sides to how we grew up: we were in the city, and very much in the public eye, and then we would be very remote, just family in a rural farm area. So I had this separation early. But I think that that mix is what has made me who I am, and also has really trained my eye. The exhibition “Mother Daughter” [in 2015 at Gagosian in New York] was about how we [Linda McCartney and Mary] had a very similar approach and a similar eye. I would say that’s when I opened the door on it.

It goes without saying your mum is seminal to your work; which other photographers informed the way you see?

I always love that Richard Billingham book Ray’s a Laugh. It’s a little study he did of his family in colour and it’s just really quite graphic feeling and very… very real life, like you can feel there’s love and laughter and arguments, all within this little book.

Also the originals, you know, the classics: Stieglitz, Steichen and Lartigue. He has a really great book called Lartigue’s Riviera. It’s him with a lot of friends; the photographs really catch so many spontaneous moments in a beautiful place.

When I first came across Gary Winogrand – he did a book called Women are Beautiful in the streets of New York – just that thing of wandering around your own area, finding little pockets of life that make you feel an emotion. To me, that’s what it’s all about. You don’t need to travel far afield to go and do a study. You can literally do it just outside your doorstep, or even in your own kitchen, or whatever.

That said, there are photos here from Japan, Hong Kong and Russia. It’s amazing what you can grasp about relationships without sharing a language, just with an attentive eye. Do you feel that body language can transcend cultures?

Yes, and not speaking a language changes things a bit. I’m glad you picked up on that. Like the one in Russia, taken with a mother and daughter… we couldn’t really communicate except by gesture, and there was a sort of trust within that. In Japan, I was there for another thing, but I thought: I’d love to see a geisha getting ready. She allowed me to photograph her from when she arrived, with no makeup on, through the whole process of making up her face to getting dressed in her robes. The woman with her in that photograph is an aunt figure who helps her. We didn’t speak each other’s language, but I felt a real connection with them when we were doing this.

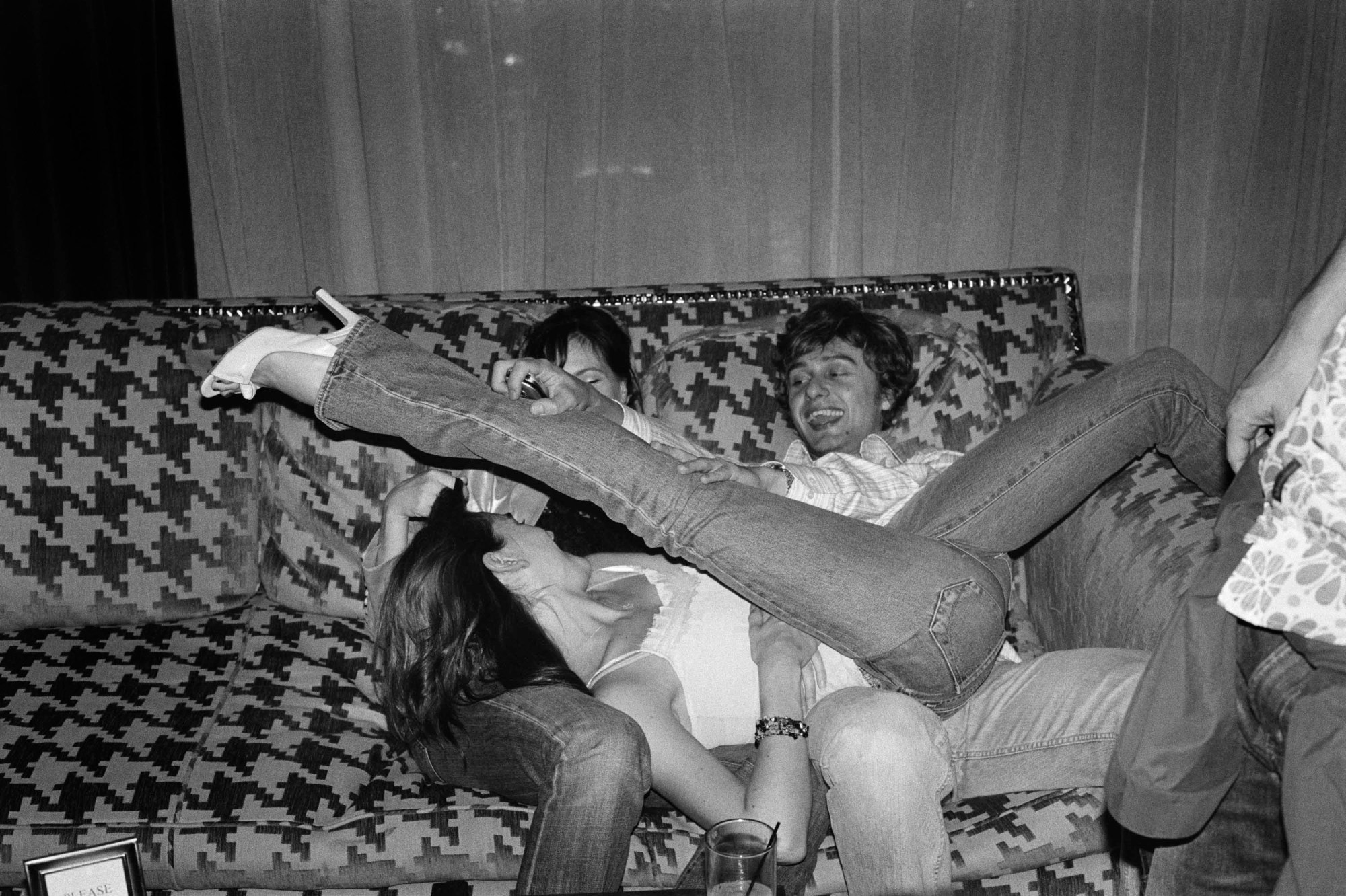

I wanted to ask about two images in particular: “Kickback” and “Embrace”, which feel slightly separate in their cheekiness.

“Kickback” was taken when I was working with the Royal Ballet dancers. I’d go out with them, following them and showing life offstage. That one I love because it shows their camaraderie and their closeness, all sort of lying around on top of each other, but also the physicality of being able to kick back that far. Offstage is what really interests me with dancers or actors — what do they do behind the scenes to get them to that point onstage.

“Embrace” is with the blow-up doll, which is funny. But then when I look at it, there’s a real romance to me, because she’s really got her back arched, and sort of really kissing with emotion, the way she’s got her wrist around the back of the neck. There’s a sensuality to it. You look closer, and you’re like, actually, maybe there’s more to the story.

I also wanted to talk about how affection slips into other moods — playful, or a bit mournful. What equilibrium were you trying to strike with these?

One side, I would say, is more poignant — like “Mother and Sister” or “Together”. If the photographs make you feel sad, it’s because you had a closeness; it’s because you’ve loved that you feel this way. So you feel sad, but then come out of it. And then it moves a bit more to celebration, a little sexiness or coy playfulness. “Hello” with the two feet, which I really love, feels very flirty. Literally it’s just the feet. Portraits where you don’t actually see the person’s face… you don’t need that sometimes. Like seeing someone’s face is almost a distraction.

Right. The silhouette actually is very telling by itself.

Exactly. I’m not putting in more than I’m interested in, and then the viewer can fill in their own narrative. The point is, when you look at it, is it making you feel something? Is it reminding you of something from your past? Are you coming up with a little story behind what you think it is?

As you were going through your contact sheets, were there other striking themes that you are now considering or assembling?

When I went through everything, it was the first time I’ve started at contact sheet 1 and gone all the way up to contact sheet, say, 5000. So I have notebooks with other ideas.

But there are other projects I’m working on — I’m directing a documentary about the history of Abbey Road Studios, which will come out in November. And my photography these days is for Feeding Creativity, a cookbook which will come out next spring. I come up with a recipe for somebody, cook it for them, and eat it with them. And then I’ll take their portrait. I’m not setting up a shoot, I’m keeping it quite casual and relaxed. I took David Hockney something at his studio; I’ve photographed Stanley Tucci for it. I just check what they really don’t like, or an allergy. You want the experience to be good. It can be quite like: …Why am I doing this? It’s embarrassing. But you come up with the idea and then you’re like, Oh! I love that challenge. When it goes well and there’s this chemistry… I love the buzz of that.

You mentioned contact sheets – do you use analog cameras?

No… although “Moment of Affection” was pretty much all shot on film. I like the texture and the depth to film. It just has a special quality — it definitely is my favourite. But I like to shoot in low light, and digital is better for that. When I shoot digitally, I always, afterwards, set it up to look as filmic as possible. I still print out contact sheets, because I like to be able to flick through them, rather than looking at the screen all the time.

And also, with film, I like having to wait. One thing about digital is you look at the screen immediately. And as you’re looking at the screen, then you’re losing a connection with the subject. Film really keeps you much more with where you are. I like when you take a picture and you can’t see it instantly, so you’re still observing the world around you.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more photography.

Credits

All images courtesy of Mary McCartney