There’s something about post-pandemic New York that reminds Mitch Epstein of the 70s, when the city was suffering from a kind of economic malaise — tortured by white flight, crime and political crises — and shrouded in the darkness of the Vietnam War. “It was a tumultuous but also a very liberating time, and I think that’s something we’re undergoing now,” he says.

Like today, the city was gritty and on the cusp of collapse, but it was spurred by artists who were able to create in a world that was less commodified. They could pay low rent, party, make mistakes and take risks, which fostered a “character that touched on bohemianism,” the photographer explains. He immortalises this in a new book Silver + Chrome, a collection of Mitch’s earliest work from 1973 to 1976, when he was a student at Cooper Union.

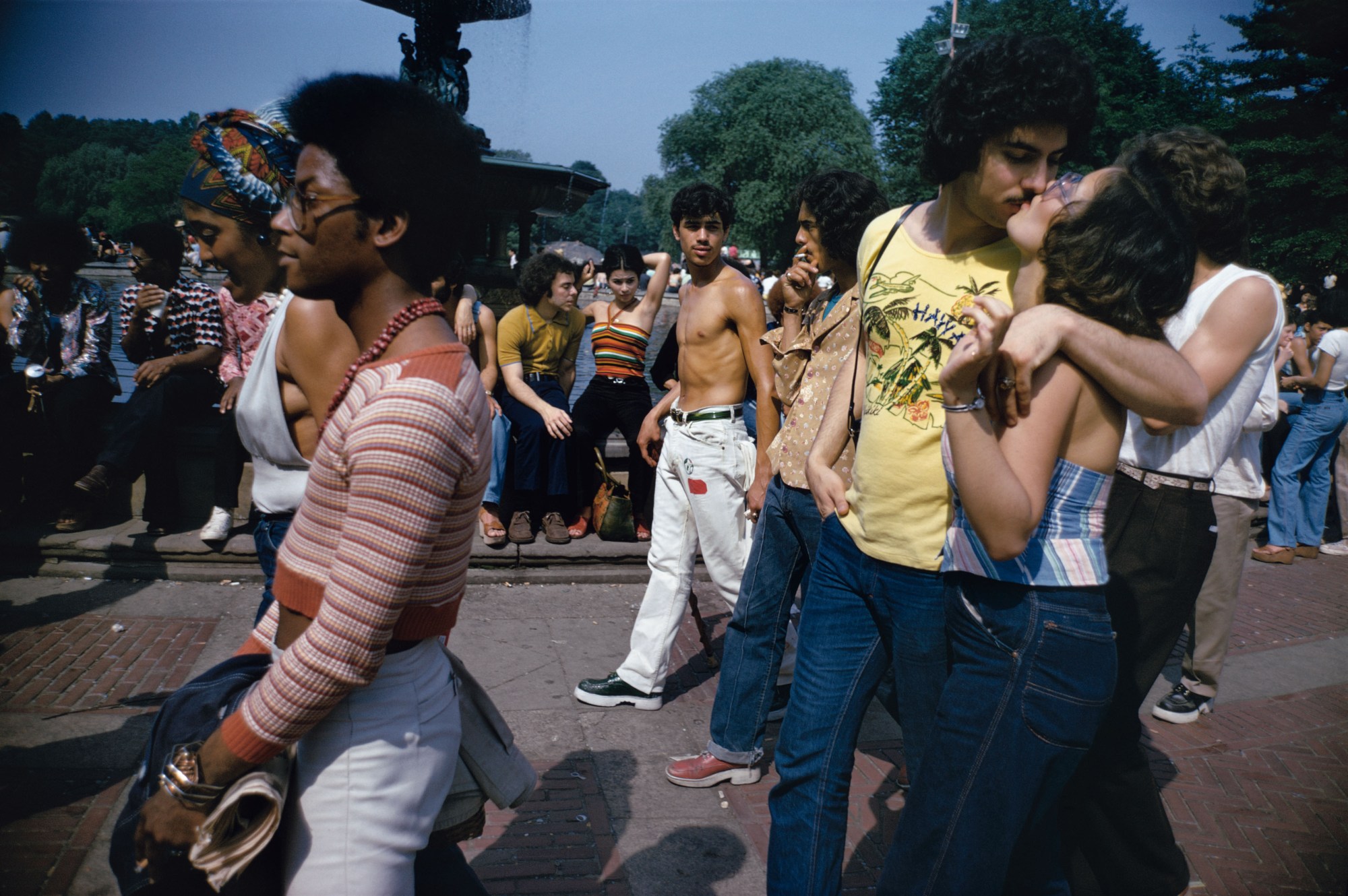

New to the city, Mitch used his camera to explore New York and make sense of it. Pounding the streets with his wide angle 28 or 35mm lens, he built tableau-like pictures — a term first coined in the 18th century by the French philosopher Denis Diderot to describe paintings that were true to life, where subjects ignored the observer and let the drama unfold around them. As such, his work is physical and athletic, standing among the people he photographed and contributing to the energy that surrounded him.

It was a challenge to “finesse and create these very pointed juxtapositions in a fraction of time,” says Mitch, who captured two women in matching leopard print coats and hats walking next to a man with a placard that read ‘help preserve the male species’. There are young couples kissing in front of a fountain, a woman with bleached hair taking a call in a phone box in the middle of a busy street and another with bouffant hair glancing over her shoulder in Central Park. These little moments, in a mad city, allowed Mitch “to carve out some kind of semblance of order from the flow and chaos of life.”

The pictures are glamorous: hairstyles are super-sized and the clothes a kaleidoscope of patterned 70s synthetics, coloured sheepskin and faux fur. Old, young, rich, poor, Black, white, Hispanic and Asian folks fill the pages, a vibrant mix of people that celebrates the diversity of the city. Though Mitch doesn’t chronicle the anti-war protests, the fights for women’s and gay rights, and environmental movements of the era, it hums beneath the surface. “There’s a lot of sexual politics and class politics. And the politics of how things play out in public spaces,” he says.

There’s one image Mitch finds particularly unnerving, taken in midtown at an event, possibly for a modelling agency, where a middle-aged man wearing a red bandana clutches at a young Black model. “This guy is so sinister,” the photographer explains, “but there’s something about a kind of sexual power interplay there that I think is very poignant. This kind of thing isn’t quite happening in the same way now. Or if it is, it’s called out.”

A black and white photograph of a group of boys on Brighton Beach coming head to head with a police car advancing on the boardwalk is similarly violent. “It’s such a jugular picture,” Mitch says. “To have these half naked bodies with the billy club in front is a startling picture in some way, and it relates to some of the times that we’re in now. Of course, everybody in this picture is white, Italian or Hispanic, but there’s something very physical in this work. It’s about the language of the body.”

Occasionally, Mitch’s subjects catch him looking through his lens, reacting to the camera with expressions of surprise or dynamically returning his gaze. One of two men with proud afros — one bleached, the other black — looks back at Mitch, posing with a cigarette in hand and an almost pout. Back then, no one had an iPhone and people were truly present in the moment.

When asked whether he could make this work today, Mitch says, “I think there’s a kind of overriding attention and a cultural conditioning to appearance, to branding, to the corporatization of the city.” This self-consciousness in the public landscape was not as obvious before — and a rawness, a carefreeness to having your photograph taken – perhaps, has been lost.

On his travels to New Orleans, Texas and Los Angeles, Mitch explored youth culture in different states — frat parties, hoedowns and carnivals — taking inspiration from the energy of the street photographers that came before him: his mentor Garry Winogrand, Robert Frank and Walker Evans. But he found freedom and his own voice through colour. At the time, the city was a cultural hotbed with independent cinemas speckling his downtown world, and a new wave of European filmmakers — like Jean-Luc Godard — contributed to his understanding of what colour could be.

Silver + Chrome is a mix of this exploration and the black and white photographs he learnt from, presented as full-bleed images that make you feel as if you’re walking the streets with Mitch. It’s immersive, physical and celebrates the drama of the situations he put himself in.

Credits

All images © Mitch Epstein / Courtesy of Steidl