During the early 20th century, when sex between men was illegal in the UK, British artist Duncan Grant (1885-1978) engaged in a series of clandestine affairs with economist John Maynard Keynes, future politician Arthur Hobhouse, and writer Lytton Strachey. Lytton brought Duncan into London’s celebrated Bloomsbury Set, a coterie of English artists, writers, and intellectuals that got its start in the homes of painter Vanessa Bell, her sister, Virginia Woolf, and their brother Adrian.

Although Vanessa was married, she fell deeply in love with Duncan, bore him a daughter, and became his companion for more than 40 years. In 1916, as World War I raged across the continent, Vanessa, Duncan, and his partner David Garnett found the perfect way to avoid conscription: farm work. Together, the trio moved to Charleston, a farmhouse in Lewes, East Sussex, which they immediately transformed into a work of living art. At the same time, they established the foundation for an open relationship, although it has been said Vanessa had eyes for no one else.

As a painter and designer of theatre sets, costumes, textiles, and pottery, Duncan was among the most prominent British artists of his time — yet the criminalisation of homosexuality forced him to establish a firm divide between the public image and true self. Born seven months before the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act, under which any male homosexual act was deemed illegal whether a witness was present or not, Duncan was just 10 years old when writer Oscar Wilde was convicted of “gross indecency” under this very act. Sentenced to two years of hard labour for “the love that dare not speak its name,” Oscar Wilde died impoverished and disgraced in 1900 at age 46. His tragic fate stood as a warning, forcing countless men to live double lives in order to avoid persecution, imprisonment, and penury.

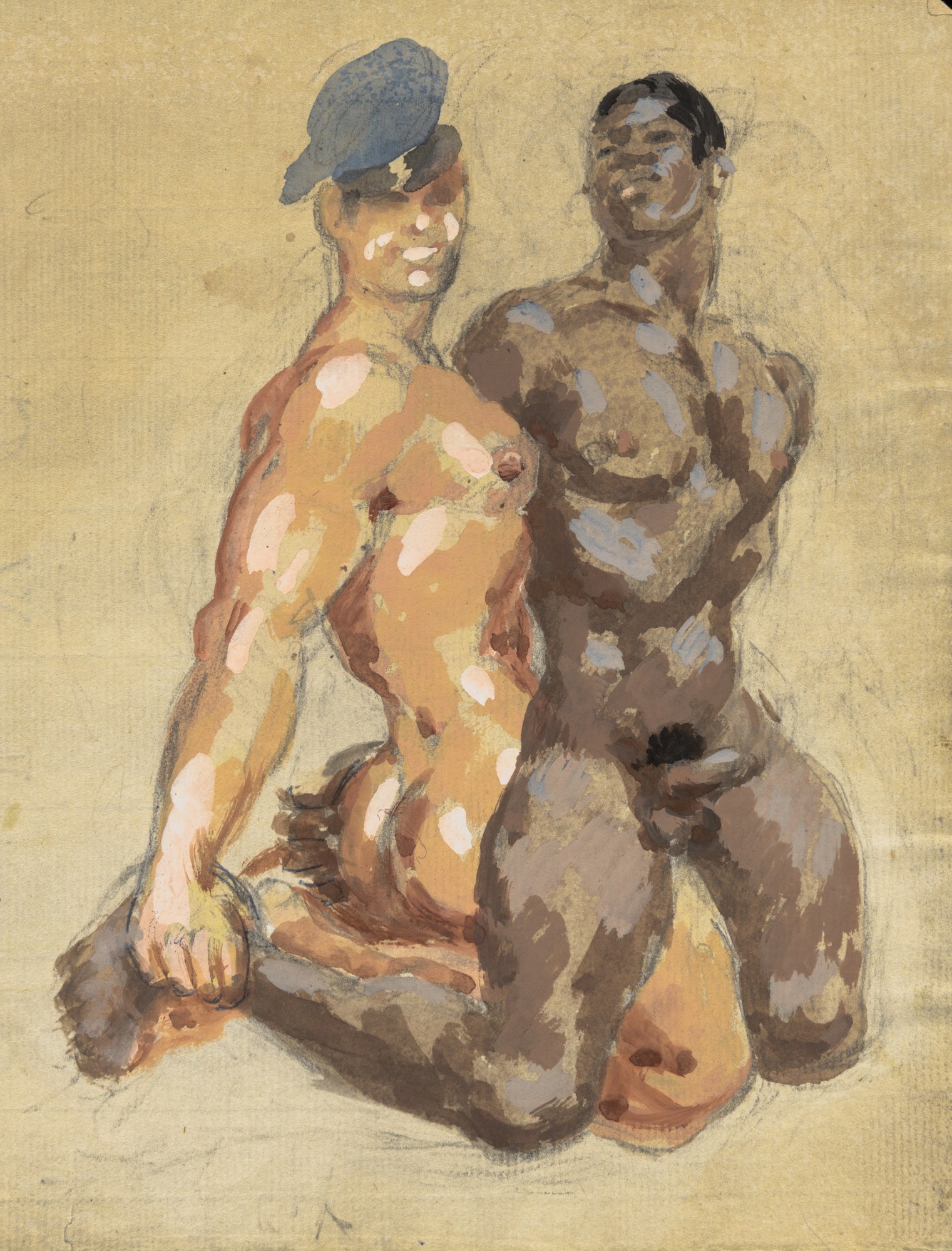

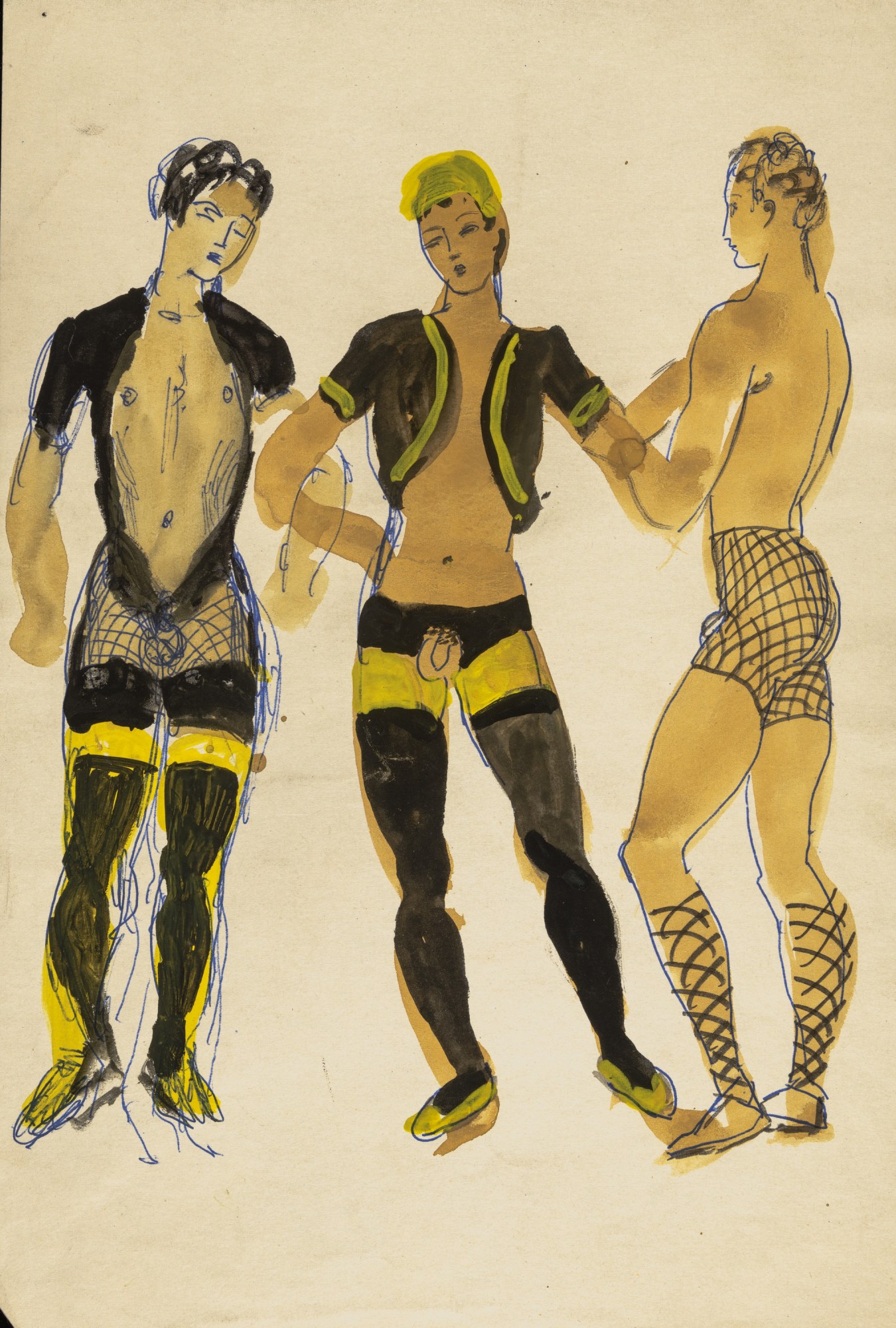

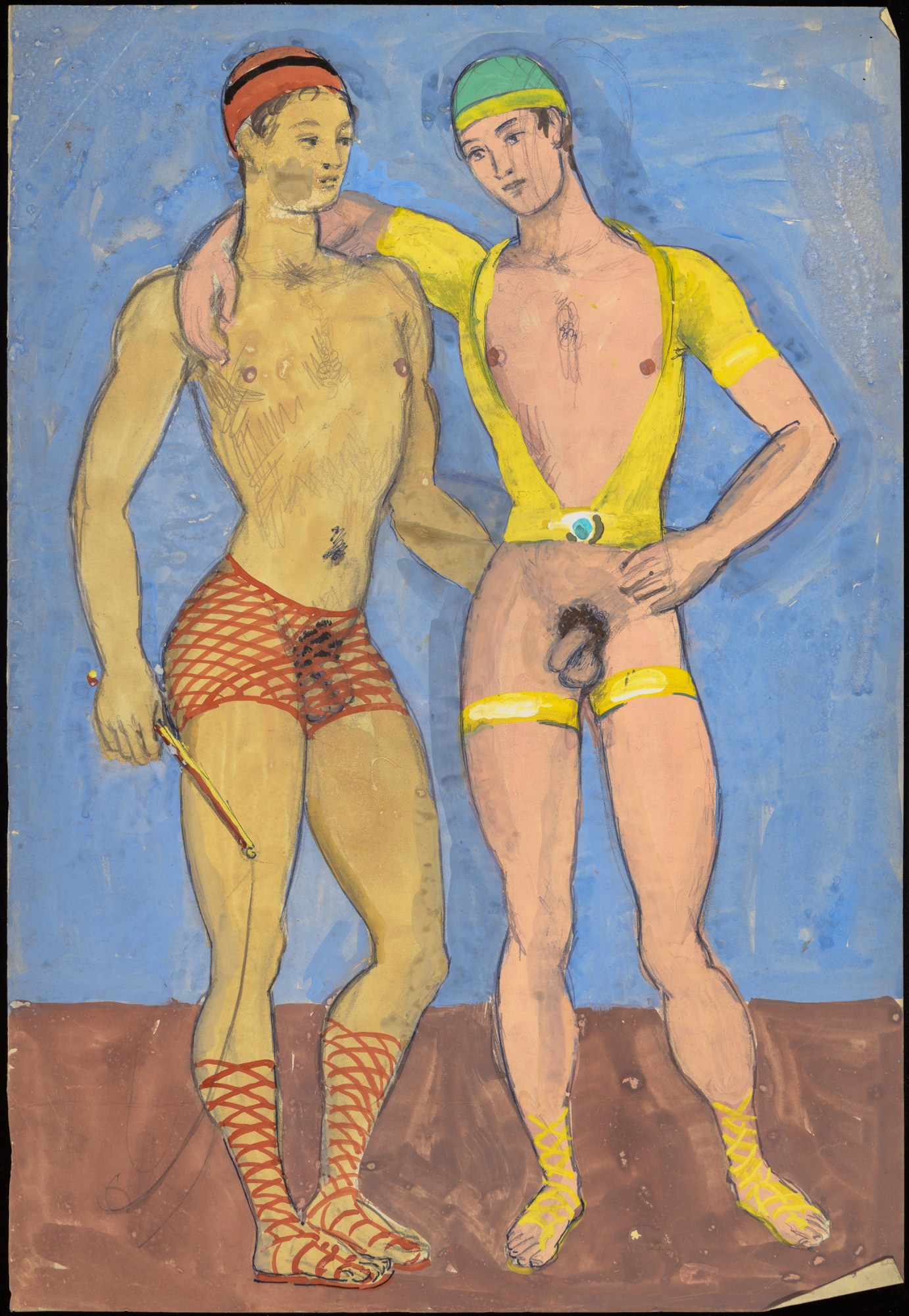

While Duncan continued to engage in illicit liaisons, he also pursued his forbidden passion for erotic art. During the 40s and 50s, he crafted sensuous drawings exploring themes of sexuality, intimacy, desire, gender, and identity. Recognising the danger these works posed in and of themselves, in 1959, Duncan gave them to his friend, the painter and collector Edward le Bas, in a folder marked, “These drawings are very private.” After Edward died in 1966, many believed the works had been destroyed, but as it turned out, they were passed secretly between friends and lovers who understood the peril of revealing the work — and their identities — in a profoundly repressive climate.

Although the British government decriminalised private homosexual acts between men over 21 in 1967, the persecution of the LGBTQ community did not stop as officials began using the Street Offences Act of 1959 to target men meeting on the street. In 1988, during the height of AIDS, Conservative politicians brought into law Section 28 of the Local Government Act, which prohibited local authorities, councils, and schools from supporting LGBTQ initiatives. In 2003, Section 28 was repealed, and slowly the tide began to turn as a series of acts introduced over the next decade finally granted the LGBTQ equal rights and protections under the law.

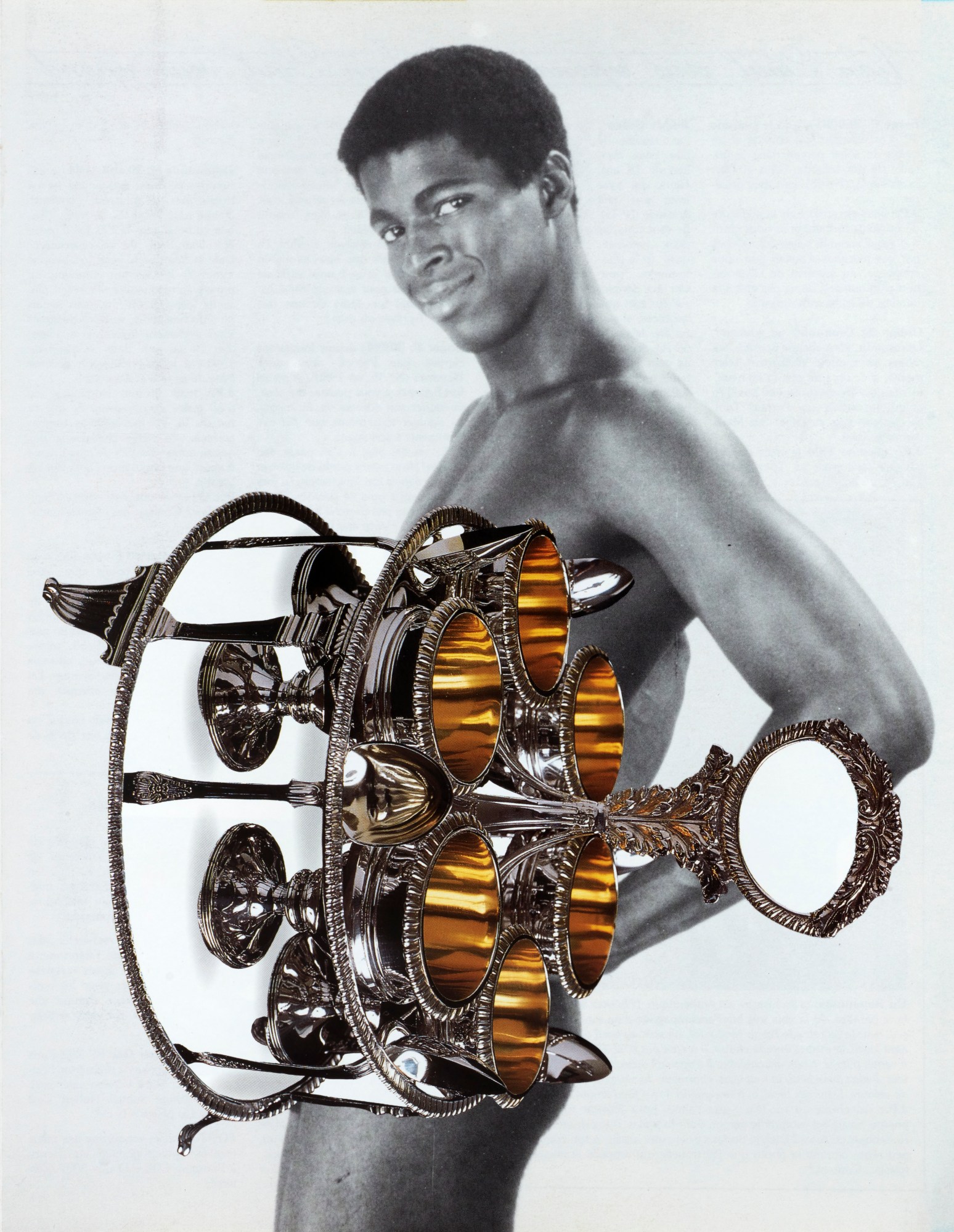

Like many queer archives, Duncan’s drawings were protected at all costs. They reemerged in 2020 when theatre designer Norman Coates donated them to the Charleston Trust — an act that made headlines as the lost collection of 422 drawings (which had been stored under a bed for the past 11 years) was valued at £2 million. Now the public will finally be able to see what has been hidden for so long. On 17 September, 40 erotic drawings by Duncan will go on view in Very Private?, which includes new responses by artists Somaya Critchlow, Harold Offeh, Kadie Salmon, Tim Walker, Alison Wilding and Ajamu X.

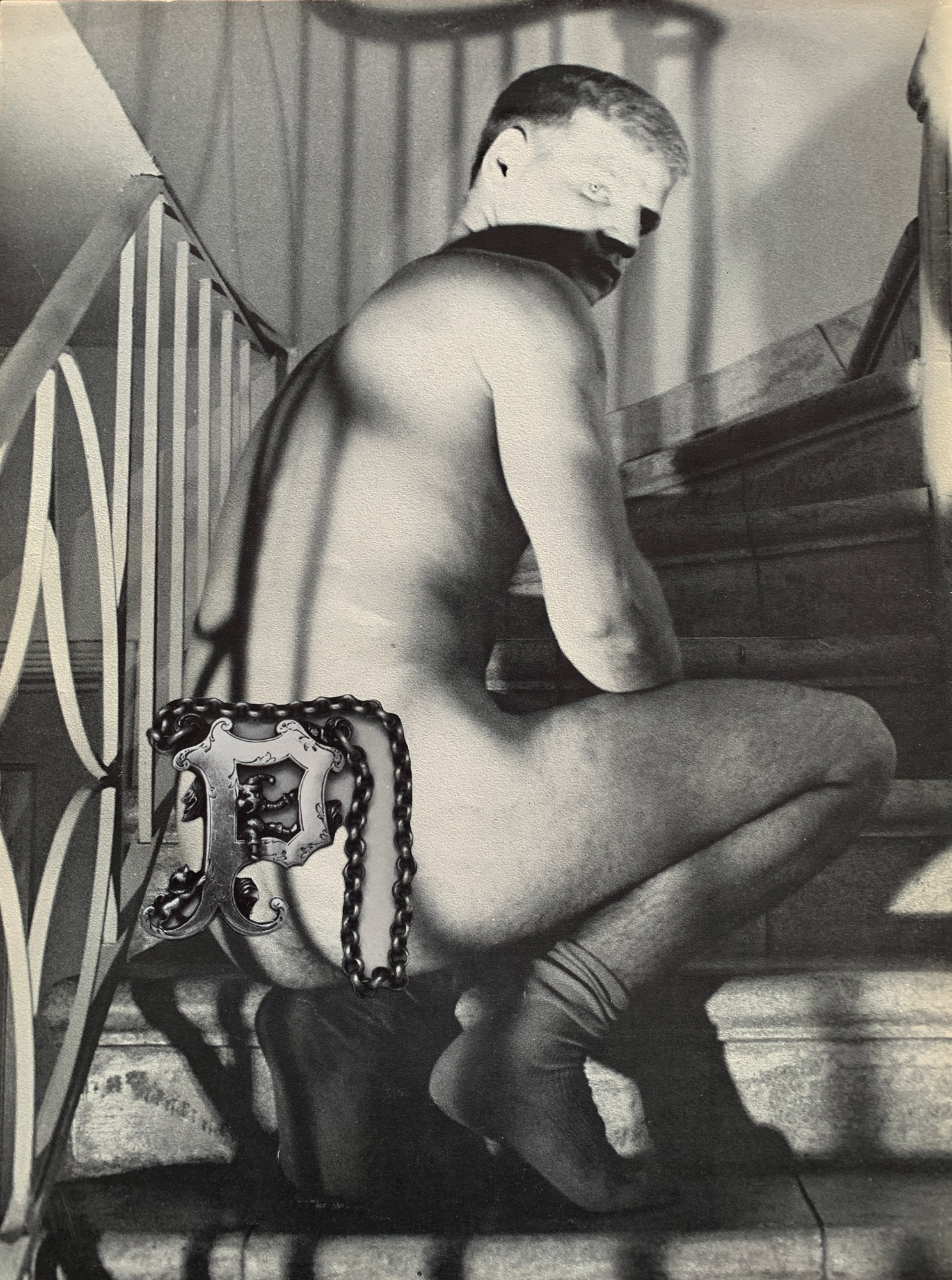

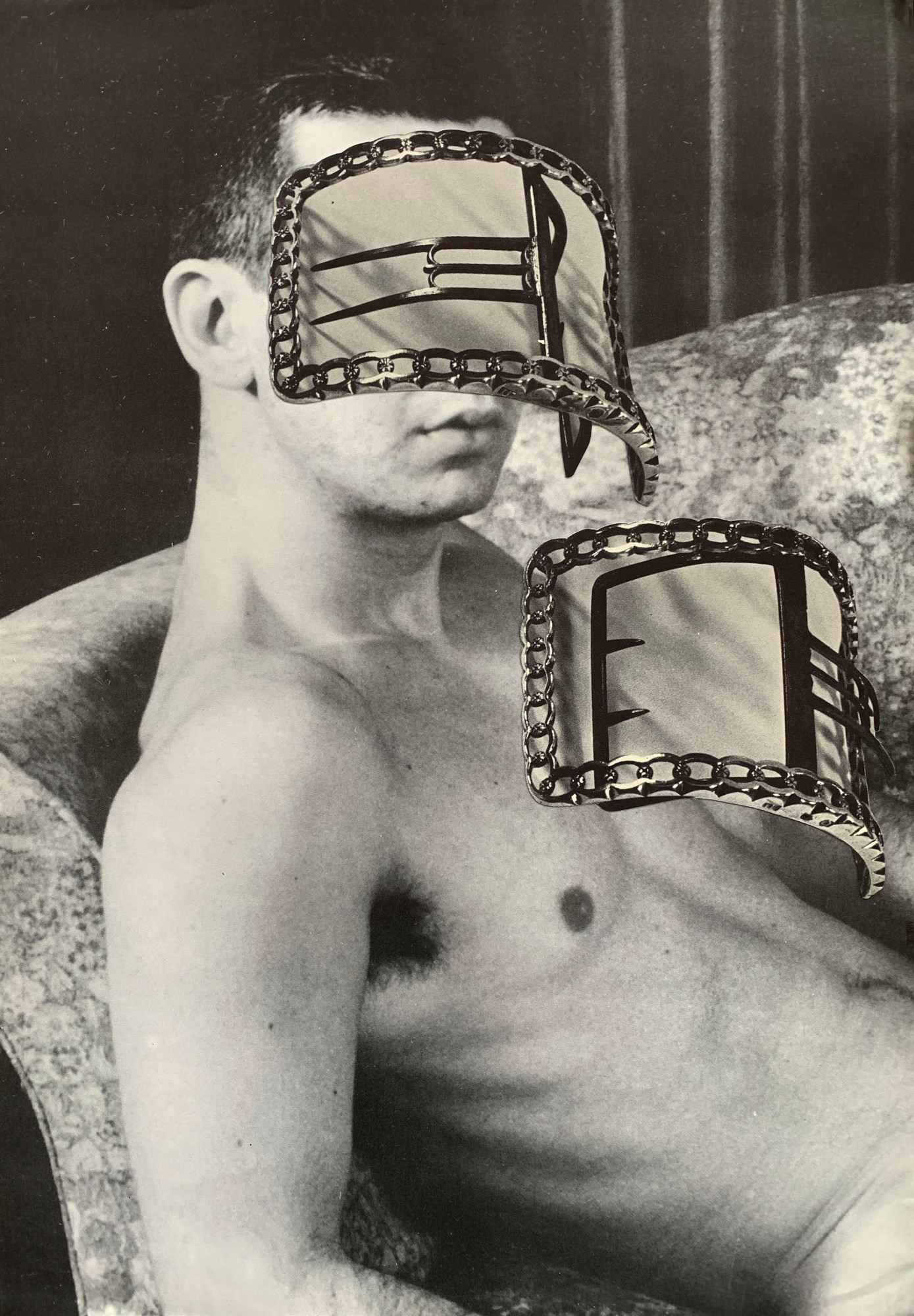

British artist Linder, best known for her radical feminist photomontage and collage works, was invited to Charleston to create a response to Duncan’s work and the environs. “When I go somewhere, I’m always hyper-sensitive,” Linder says. “My whole body is wide awake, trying to absorb the atmosphere. The investigation is multi-sensory.” In dialogue with Duncan, Linder presents A Dream Between Sleeping and Waking, a solo multimedia presentation featuring never-before-seen series of works made for the Houston-based producer and musician Rabit, featuring the contemporary queer music collective House of Kenzo.

“I’ve always been fascinated with glamour, its ability to cast a spell and enchant,” Linder says. “The first imagery I was shown was glamour photography, so from a young age, I developed this antenna where I could measure it like people measure radioactivity — and it’s not necessarily beautiful.” Rather, it is spellbinding, much like a dream, weaving you in a web that transcends logic and reason.

Linder recognised this sensation travelling through East Sussex. “The hills of the countryside are quite undulating, and then you arrive at a small farmhouse,” she says. “Charleston is very seductive. It was designed to be deeply pleasurable, very sage, and liberated. You get the sense the house never switches off; it’s always on, always performing. It’s so beautiful and bewitching. It has this extraordinary history of its inhabitants and the tangled relationships happening there.”

Mesmerised by the exquisite paintings Vanessa did directly on the walls, Linder found herself surrendering to the hand of the artist as it enveloped her in the magic and mystery of Charleston. But Linder, with her lifelong predilection for glamour, fantasy, and subversion, immediately recognised a curious dissonance between image and reality. “I began to see the house as a hideaway because, for the first 78 years of Duncan Grant’s life, he was considered a criminal because he was homosexual,” she says. “Being upper middle class, perhaps it was easier to hide from the public eye. I think of the house as a form of social camouflage and decoys. The surface can act like flypaper, and people can get stuck on the glamour without going behind it.”

“The lands are a fading lucid lens between the dream and everyday life, and when one is working with these houses that have a daunting history at times, you can see there’s something very subtle and very powerful happening underneath. How is this happening? How is something making me feel quite sleepy and want to curl up on that tiny bed of Vanessa Bell’s and wake up with a ghost? I don’t have the answer yet.”

Perhaps that is the state that Duncan described when looking at the paintings of Belgian surrealist René Magritte: “A dream between sleeping and waking,” which inspired Linder’s exhibition title. It’s a curious space, made all the most surreal by the contrast between the landscape of Charleston and the lives of its inhabitants. The environs are romantic in the 19th-century sense of the word: the sublime expression of the human experience, where grandeur and ruin meld with the seen and unseen, so that waking life starts to feel more like a dream.

Linder references the 1973 Roxy Music hit, “In Every Dream Home a Heartache”, a truth some know too well. “I always look for the heartache, typical northerner of Irish descent. I wonder, ‘What’s happened here? Where is the dream home? What was the tragedy?’. Maybe that’s more to do with a gothic imagination, but that’s what I’m trying to dig out. Money and class are no protection against scandal. If you’re vaguely aristocratic and you’re caught for homosexual crime, then it’s amplified.”

Though Duncan could not publicly express his true self, he refused to sacrifice his creativity. Linder speaks breathlessly about the drawings, some of which are no larger than the size of cigarette packets. Many are done on magazine pages, others on newsprint, never the heavy substrate used for longevity and permanence. “Everything is very ephemeral. They don’t carry a weight. They’re not laboured and don’t seem premeditated. It’s almost scribble, and when you are looking at them, its very exciting,” Linder says.

In Duncan’s hands, these works are both evidence of a crime and an act of liberation itself — an energy that is alive and even contagious. “These are drawings you can hide and then unfold for this glorious moment when you’re going through the folios,” Linder finishes. “They felt so delicious! I have to start drawing again. I’m grateful to the ghost of Duncan Grant that leads me back to pen and pencil again.”

‘Very Private?‘ and ‘Linder: A Dream Between Sleeping and Waking‘ are on view 17 September 2022 – 12 March 2023 at Charleston in East Sussex.