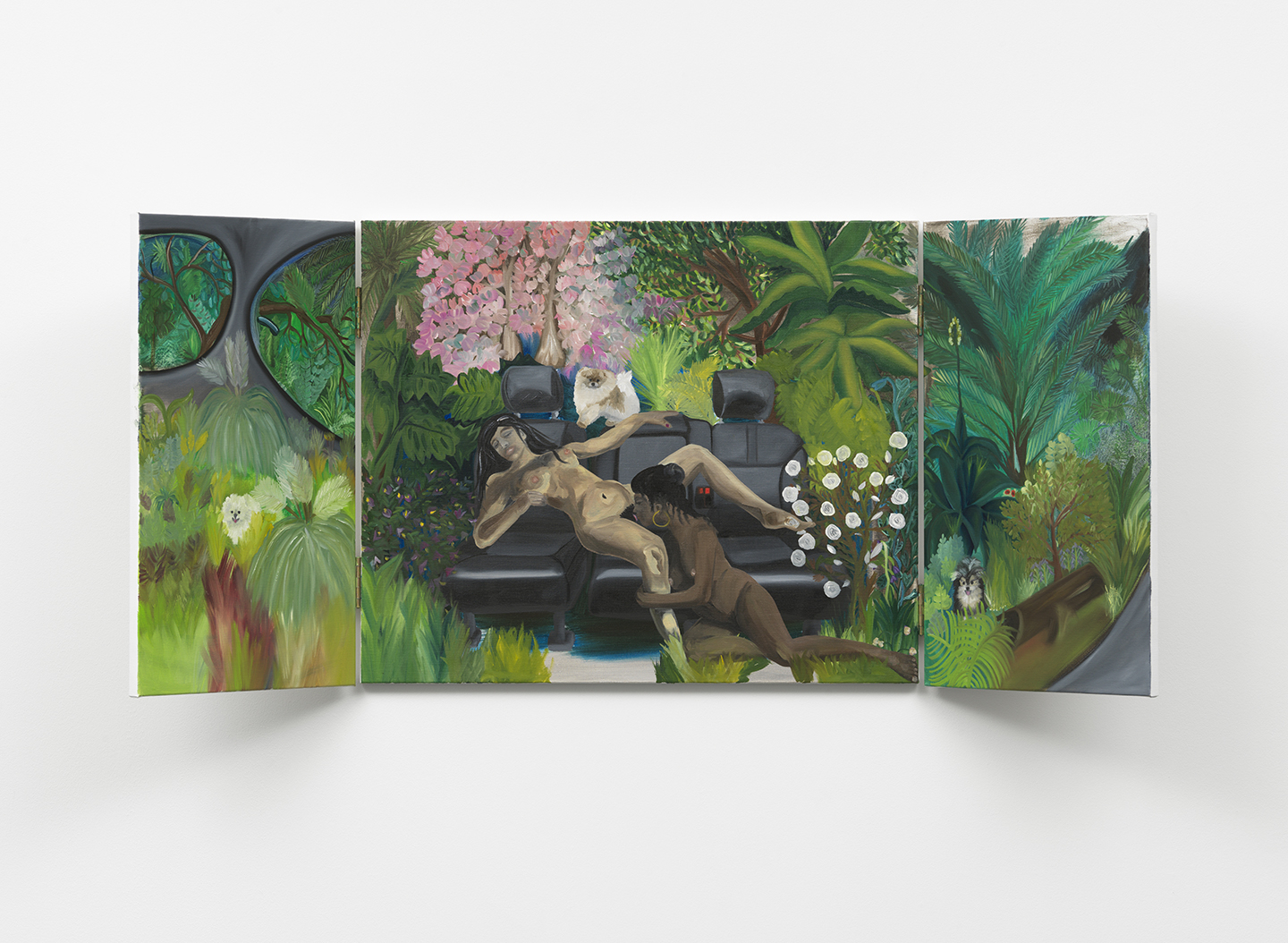

With work themed around driverless cars, cosmic travel, queer ecstasy and lush vegetation, Mexican painter Frieda Toranzo Jaeger enmeshes kitsch and catastrophe, erotica and agitation. Her vivid multi-paneled paintings, incorporating shapely ceramics and traditional Indigenous embroidery, jostle gendered tropes, turning absurd symbols of heteronormative virility into sanctums of queer bliss. Cars — an image traditionally approached with aggressive masculinity in art — are subverted: Frieda turns their backseats into sapphic divans and transforms dashboards into art historical riddles.

Her unconventional canvas shapes — hinged together and best experienced from many different angles — push against the art history rules that have so often excluded women, Indigenous voices, and queer identity. What’s more, she integrates her family’s proud lineage of craftsmanship into it, hiring them to embroider her canvases. (“They often think contemporary art is weird, so this is how I bring them closer to what I do,” she once said.)

“She’s thinking about how altar paintings were also a tool for colonialism and the spread of Christianity and religion,” Ruba Katrib, the curator of Autonomous Drive, a MoMA PS1 exhibition of her recent work, says. “You see in the panel paintings the way that she’s thinking through nonlinear narratives. They’re sculptural: not a flat surface that you’re reading. You need to move around and physically engage with it.”

Here, Ruba speaks about Frieda’s work in depth: the LGBTQ sanctuaries she creates, the unexpected spin she puts on German Renaissance paintings and the potential that arises from destruction.

A sense of playfulness definitely comes across in Frieda’s work. It feels like a little wink.

It’s not meant to be didactic at all. [She’s] playing with the themes and turning them on their head, and there’s so much history she’s evoking too.

Frieda talks about the apocalypse. According to a lot of people, the apocalypse already happened or is happening. It’s this idea of complete collapse and change happening all the time.

But she makes it look like a utopia can be extricated from all the burning happening adjacently.

Exactly. And if you look at “For New Futures We Need New Beginnings,” this column is quite ambitious. The work has a console on which you have all these different art historical references. You see how travel has been so key to globalization [and] the history of colonialism. And you see Eve and Eve instead of Adam and Eve.

The vehicle motif — mostly cars, but here something more interstellar — is a constant through line.

She’s interested in the ontological shift that’s taking place from this masculine driver to the more passive passenger role. “Sound System Idea on 110 North (LA is a Bad Reality Show)” is a new piece that she made for the exhibition. It’s the first time she’s bringing in even more sculptural materials: ceramic pieces that she made while she was in LA teaching for a semester. It’s very much inspired by the time spent traveling in the car.

I think what she’s doing with painting is so radical, breaking away from linear representation. I just have not seen painters working on canvases like this. Artists use shaped canvases, but I think she’s really taking it to another level playing with the idea of sculpture, painting and craft by stitching or using fabric or other materials. It’s this construction of the picture plane, decorating it.

As you mentioned, present and future are confounded, creating a kind of muddy timeline. Do you think her point of view is still hopeful?

[Her point of view frames] destruction and reinvention as a continuous process. It’s new possibilities that open when there is destruction or collapse. The queer futurity… there’s all this projection of the idea that you’re always becoming. I think that’s a point that she’s really invested in: this idea of continuous realization. It’s never an end point.

Although the cross-section of materials she’s using is quite singular, who would you situate her amongst in terms of other artists?

I would think of Nicole Eisenman or Leidy Churchman — people that are really playing with the medium of painting. But even the other show that’s on that I organized in conversation with Frieda, Umar Rashid… they’re two distinct shows, but sitting next to each other, there’s a dialogue in some way. He’s an artist who’s from Chicago, based in Los Angeles. And he has a very specific narrative that he’s working on: empire and the creation of New York in the 1700s. But, again, looking through this idea of history painting and creating alternate stories, using history to talk about the present, to talk about the future. That kind of crossing through time, I think, is something they have in common.

In previous interviews, Frieda talked about how she felt painting was maligned today as a medium with political potential. Do you also feel that’s true?

I think it’s really true. I think that painting is always political, but it’s the content — like putting a political message in the content — that’s less common. I think she’s doing something very distinct and fresh right now.

Especially taking up so much space with her paintings…

Frank Stella has these, like, crazy sculptural paintings. But these feel very different. There are some precedents, but she’s literally turning the painting into, like, the shape of a car! The narrative is entering the form. That’s what’s so unique.

Especially for “Hope The Air Conditioning Is On While Facing Global Warming (Part I)”, there’s a kind of absurd 80s movie quality it evokes, although I can’t pinpoint which one. Probably something with young Tom Cruise.

It’s very “Back to the Future”.

Oh yes — true!

Every time I come in here, I see something different or notice something else with the work. It just keeps unfolding.

‘Frieda Toranzo Jaeger’s Autonomous Drive’ at MoMA PS1 is on view through March 13, 2023.

Credits

Images courtesy of MoMA PS1

Photos vourtesy of the Artist, Tim Bowditch, Jens Ziehe, and Steven Paneccasio