The story and spirit of Guåhan, or Guam, find their roots with Fu’una, the creation goddess who gave the CHamoru people life. It all started with her brother, Puntan, who gave his body to create the earth and heavens. Fu’una then created more life by transforming into Lasso’ Fu’a (Fouha Rock), from which the first humans sprouted. For the CHamoru people of the Mariana Islands, life itself started with a famalao’an — a woman.

For CHamoru artist Gisela McDaniel, it all started with a self-portrait. The Detroit-based diasporic Indigenous artist first began exploring what healing from sexual and colonial violence could look like outside of a linear framework through her art. She allows for subject-collaborators, who are primarily women of color and non-binary people of color, to share their stories, which in turn inform the paintings’ compositions and reclaim control over their narratives and healing processes.

“I got to a place where I just felt bad about my sexuality and body, because it seemed to have gotten me into so much trouble, and [painting] is how I started to build that relationship back. I wanted to offer that to other people,” Gisela says. “I really make the paintings for the subjects. The subjects are not there for you — they’re there for themselves, to tell their stories. The painting is not a decorative object. It’s not something for your pleasure, it’s for theirs.”

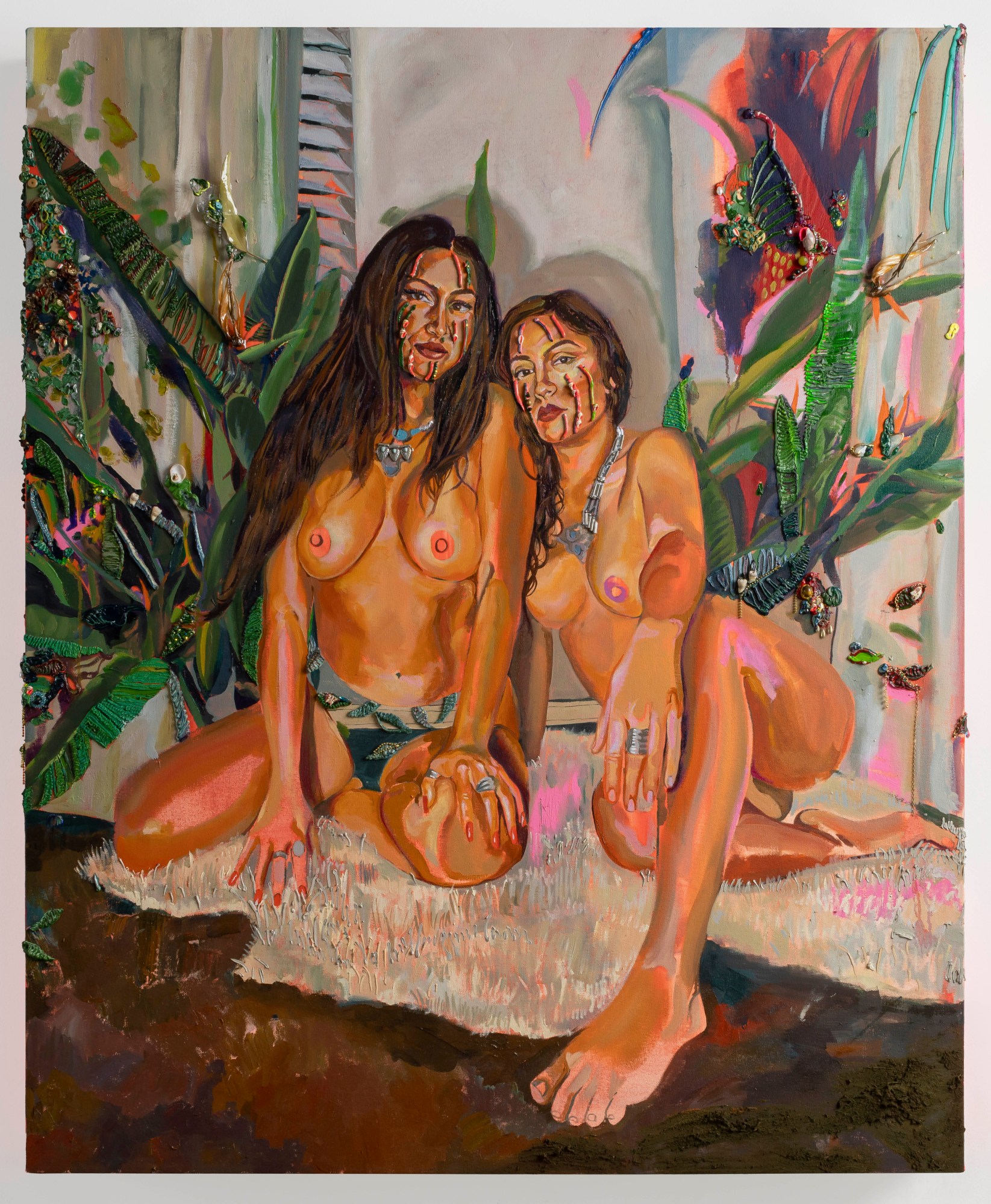

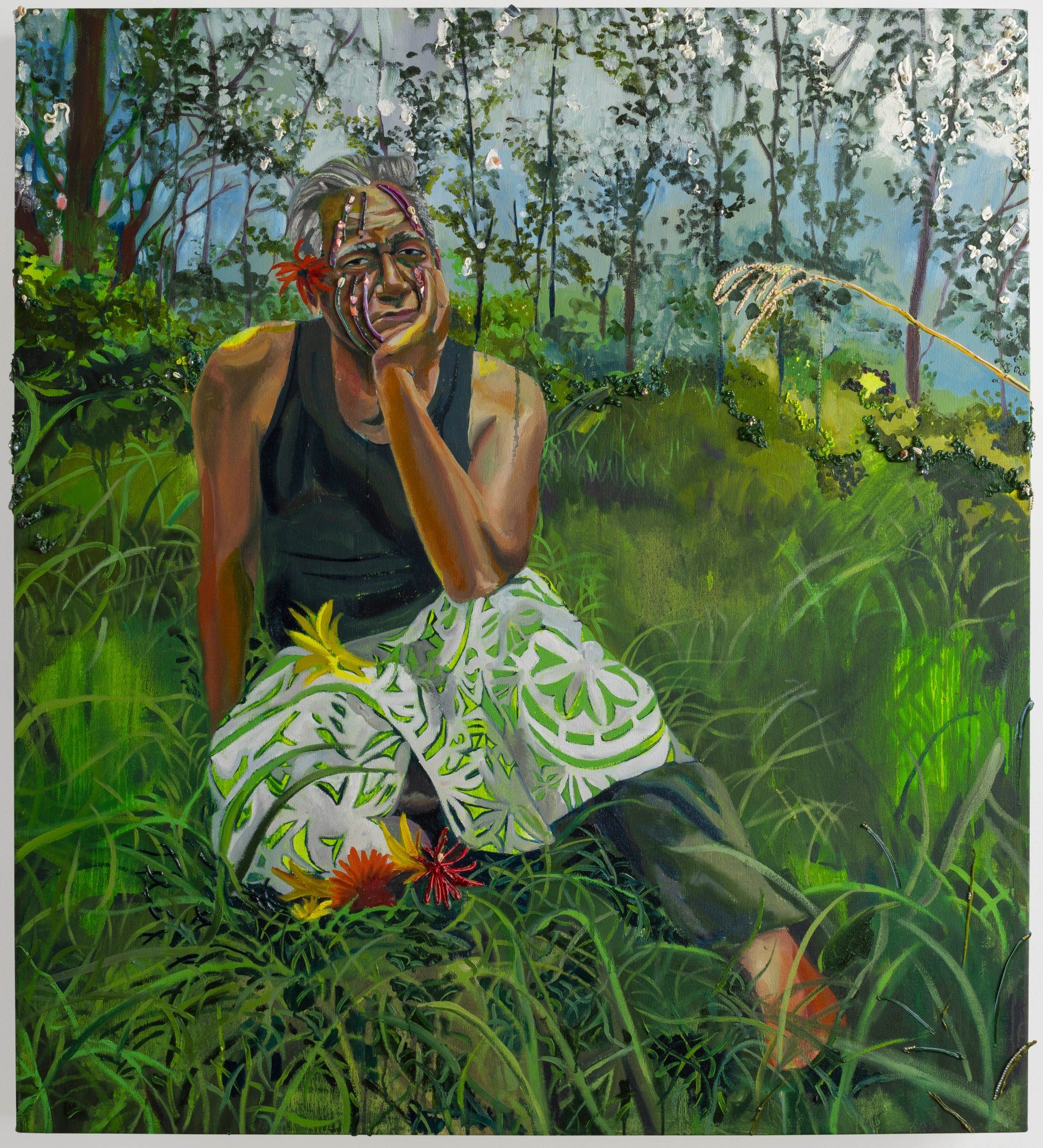

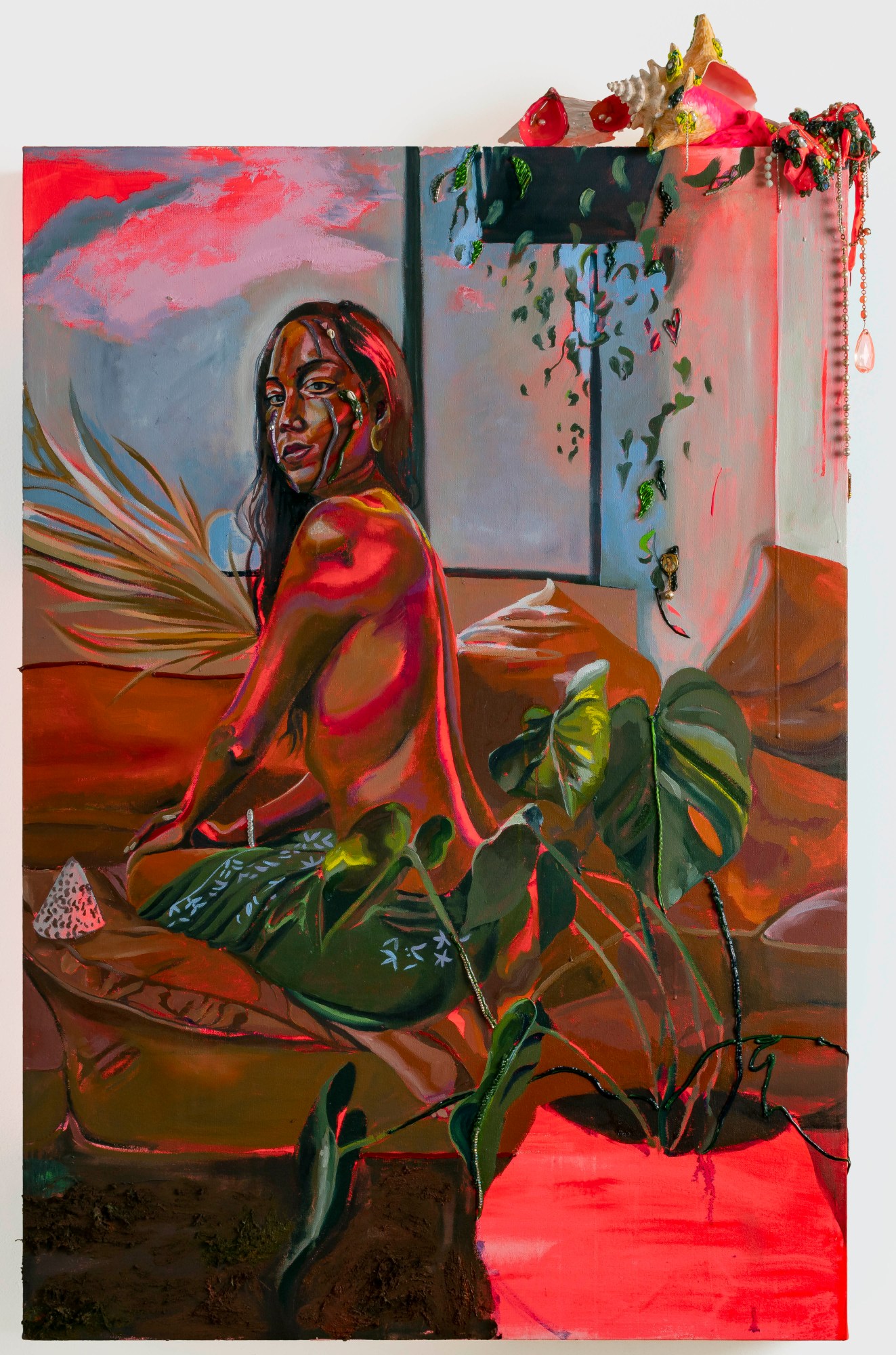

Gisela’s solo show at the Pilar Corrias gallery in London, Manhaga Fu’una, meaning “Fu’una’s daughters” in CHamoru, attests to the very spirit of creation, from the colorful paintings that alchemize the colonial, hierarchical art tradition of the violent voyeur and sitting subject (looking at you, Gauguin) to reclaiming the power of a centuries-long legacy of resistance. Gisela’s subjects hail from Guam and American Sāmoa, former European colonies that remain US territories today. The title of the show and individual pieces are deliberately in CHamoru to help protect the endangered language and to keep the works grounded in ancestral roots.

“Showing work in London is interesting because it’s like the capital of imperialism and colonization, so I feel the pieces need an extra layer of protection, putting them in this space,” Gisela explains. “The main goal is to make sure everyone is very dignified. Painting, especially with oils, is layers, but that first layer for me is that relationship I have with the people I’m painting. I don’t care if it’s something that a collector is going to be interested in. [It’s] much more a collaboration than a piece I’m producing on my own because I am reflecting on the story — I am reflecting on what it’s like to sit with somebody in a room and what that felt like.”

Gisela’s work incorporates a multimedia approach, featuring audio recordings of interviews with subjects and objects both found and donated that join evocative strokes on the canvas. “People contributing objects is special when you think about artifacts and museums — especially here, [where] it’s all stolen. So to ask somebody intentionally and consensually, ‘What do you want to be remembered with?’, whether I’m just painting that object or it’s a literal object — like a wisdom tooth or broken necklace — is not something that’s necessarily shared with the outside world,” she says. Past subjects have even dropped off old jewelry for Gisela to use in new paintings as an act of solidarity. “I just see all these circles of connections with the people I paint. The audio is becoming a chorus — there’s more of them, and they’re coming together, louder. I also have a recording of one of the aquifers on the island, just to let the land speak. It feels almost like building, not an actual army, but a chorus of voices and stories that are this ammunition that we have to recognize and honor.”

Gisela’s show is a rare instance of indigeneity being celebrated, rather than exploited, by an art world that often reflects the real world in its infliction of harm and erasure upon Black, Indigenous and other communities of color, as opposed to the lofty ideals it espouses. Protection is emphasized throughout her work because many of the stories her collaborators shared wouldn’t have happened had they not been targeted for sexual and racial violence due to the white supremacist patriarchy’s violent comportment for women of color, non-binary people of color and their Othered intersections of identity. Conversations between Gisela and her subjects are about more than their traumas, however; they’re identity-based, rooted in their familial upbringings, reflections of what makes them proud and what healing and joy look like. Subjects are allowed to choose how they want to pose, nude or otherwise, in order to return the right to consent to subjects.

“When I first started this work, a lot of people would see the paintings and immediately sexualize them and make assumptions. It feels really re-traumatizing and wrong. I want the [subjects] to have as much presence and control over their own narratives as possible. Once it leaves my studio, I can’t control who’s looking at it, who comes to the shows, who’s walking into the gallery — but I do everything in my power to put protection into the work and make sure they’re painted the way they want to be painted.” Gisela explains. This prompted her to even use canvases that are about six inches thick, reinforcing subjects’ space and boundaries. “It’s because I want them to have a physical body and presence that you have to acknowledge and honor when you approach them.”

Another reason Gisela documents these stories is because of how much has been lost from over 500 years of colonialism and imperialism worldwide — and because what little has been documented is unfeeling, harmful and from a colonial gaze. “So much has been lost. Something that’s really important to me is honoring the emotions we have through experiences, because in data and statistics, those emotions are never honored. I don’t know how far I believe empathy can go, but I think it’s important to try. When you tell somebody how something made you feel, you connect totally differently to it.”

Millennia-old CHamoru values that are intrinsic to Gisela’s artwork are also reflected in her advocacy for the community; most specifically with water protectors such as Protect Guam Water and Prutehi Litekyan, or “Save Ritidian” — a Guam-based group opposing further militarization of Indigenous land. Additionally, her advocacy encompasses women and queer people’s safety on the island, from supporting famalao’an on Guam who are fighting for access to abortion to providing awareness around Guam having the second highest number of reported rapes per capita in the US. Sexual violence and trauma are pervasive on the island because of its highly militarized status. While there are the broader cultural issues of American patriarchy and military sexism, as well as patriarchy on Guam shaped by colonial rule under Spain, Japan and the US, one of the most pressingly brutal effects of military presence is sex trafficking and environmental degradation. For Gisela, these issues are not disconnected from her art, just as her art is not disconnected from her identity. A question she asks subjects is, “How do your experiences affect the way you move?”

“Being on Guam, the importance of trust really became more clear to me. I felt at home — everybody felt like family. I had a new awareness of the respect that I needed to have going into interviews with people I painted,” she says. “Something [else] that kept coming up in conversations was how they felt that dance was taken from them, and they felt like they weren’t free to go to a club to dance because it felt like you were inviting someone to touch you if you did that. Because of the military presence on the island and the way that space on the island isn’t yours, you literally can’t move in a joyful way.”

Gisela’s paintings comprise an expressive and impressive lexicon of what it means to be human and just how resilient the human spirit is after all. With every vibrant brush stroke, every object hidden in plain sight, every story shared — she never ceases in the pursuit of collective healing and joy, defying history’s harmful narratives, and affirming the right to protection, peace and being honored.

“I’ve learned so much more from my peers than I could ever learn in any American textbook. The way people survive is so graceful, but it’s also so quiet. It’s such a private thing, so I feel really lucky to have people trust me enough to sit with me and tell me these things — making sure that people are painted into history, the people I care about. The stories are precious. The people are precious. At the end of the day, this is the history I want to read about. This is the history I want to see.”

Manhaga Fu’una is on display at Pilar Corrias in London through 26 February 2022.