“For years, I’ve been telling myself that the reason why my work is often unacknowledged is perhaps that it is ahead of its time,” says Brooklyn native Marcia Resnick. “The work I made over 40 years ago is finally in demand!” With the new touring museum exhibition and catalogue, Marcia Resnick: As It Is Or Could Be, the photographer is finally getting her due, with the first comprehensive survey of her highly influential work made in downtown New York during the 1970s and early 80s.

A pivotal figure on the scene, Marcia used the camera as a tool of conceptual art long before the mainstream recognised such a notion. For as long as she can remember, art was an integral part of her life. As a teenager, she revelled in the thrill of traveling to Manhattan every Saturday for an art class at Washington Irving High School in Gramercy Park. After school, she would walk down to Greenwich Village to hang out late into the night at bohemian mainstays like Café Wha? and Café Au Go Go, listening to local bands like The Blues Project.

After graduating high school at 16, Marcia received a full scholarship plus living expenses to attend New York University. Two years later, she transferred to nearby Cooper Union to focus on her art studies. “It was just wonderful living in the East Village at that time,” she says. “All the best artists were living in New York, and were available to come and talk to students.”

While studying drawing and painting, Marcia developed a complicated relationship with photography. “I fell in love with it — but I didn’t believe that just snapping a picture could result in the creation of real art,” she says. Then she learned about Allan Kaprow’s Happenings, something which blurred the distinction for her, and led her to study “Post Studio Art” with John Baldessari at California Institute of the Arts. Embracing conceptual art, Marcia realised that by staging her photographs she could express herself on her own terms.

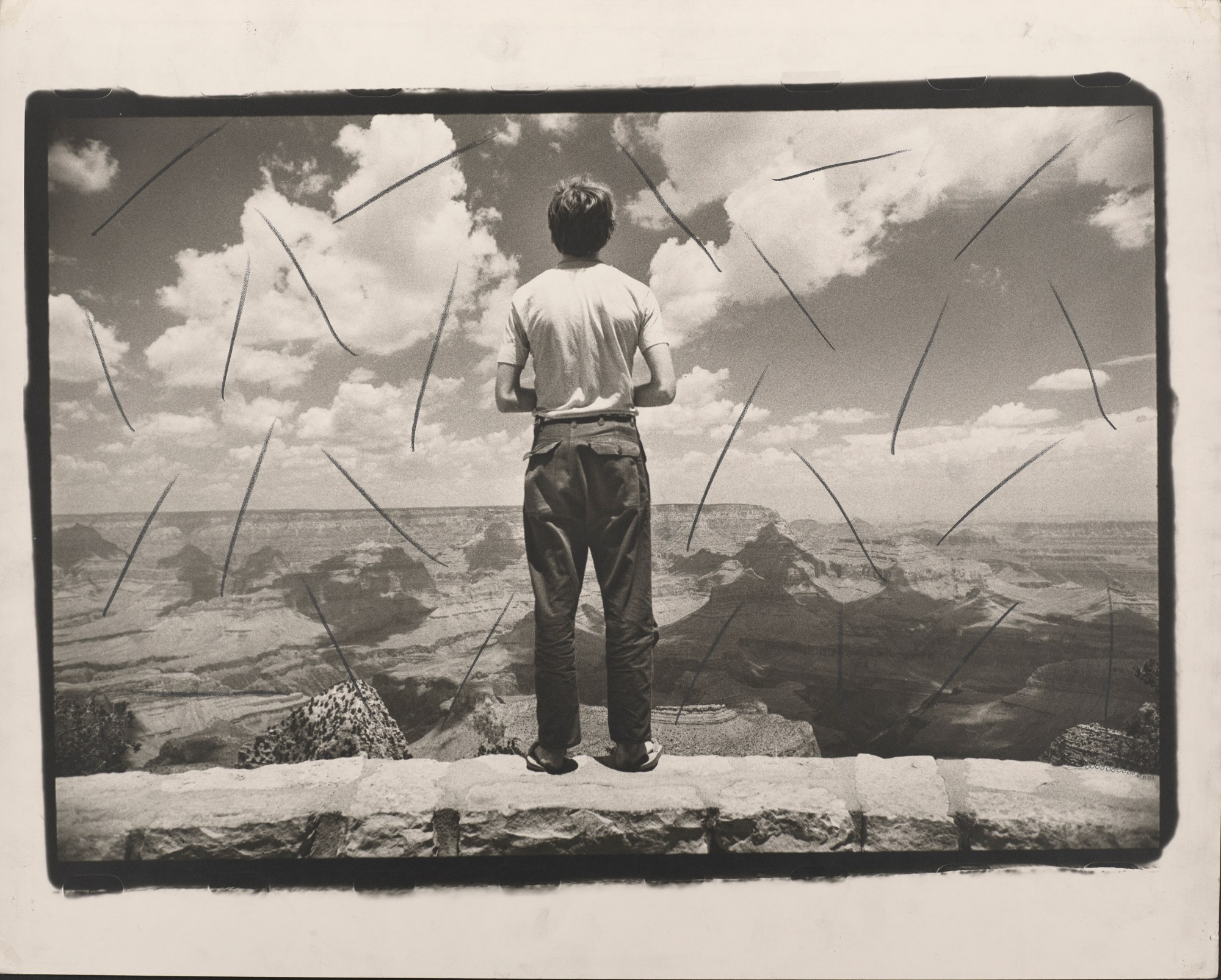

After receiving her MFA in 1973, Marcia secured a teaching position at Queens College and embarked on a cross country road trip back to New York in her car, which proudly bore the words “Marcia the Masher” across the passenger side. Marcia shared an apartment on Bowery and Houston Street with artist and dancer Pooh Kaye, and split the mere $140 a month rent. “People from all over the country were moving to New York because they could afford to live here,” she says.

Long before downtown New York became a neoliberal playground, it had been abandoned and left for dead when manufacturing fled downtown Manhattan during the 1960s. Unoccupied, massive industrial buildings constructed after the Civil War began to rot and fall apart, literally crumbling onto sidewalks. Although Soho and Tribeca had been given chic new portmanteaus coined by real estate developers who saw the possibilities of gentrification long before most, it would be years before such neighbourhoods were considered liveable.

By the early 1970s, Manhattan was truly romantic, in the 19th-century sense of the world: a sublime state of ruin, its grandeur now a thing of the past. Plagued by a fiscal crisis that pushed the city to the edge of bankruptcy, radical budget cuts to municipal services, a mass exodus of the middle class, landlord sponsored arson, a 12.5% unemployment rate, and skyrocketing crime rates — New York was a former shell of itself.

Into the void, a new generation of artists, musicians, writers, filmmakers, and dancers set forth, drawn to an intoxicating blend of cheap rent, massive space, great light, and outlaw atmosphere. They transformed barren lofts into artist studios, fostering a sense of community and camaraderie among those who found no comfort in the trappings of the bourgeoisie. For many, there were no amenities, let alone basic necessities like heat, but this new generation of artists were young, hungry and willing to do whatever it took to live by their own wits and remake art in their image.

In late 1974, Marcia found a building on Canal Street down by the Hudson River that had dilapidated 2,000-square-foot lofts available for rent above a city-run methadone centre. With 14 windows and a river view, Marcia was home — and made sure to extend this opportunity for affordable housing to other artists in need. After seeing Laurie Anderson give a performance about losing her loft in a fire, Marcia invited her to move into the building.

Marcia remembers the art scene of the 70s as one of community, camaraderie and fun. The collectivist approach extended beyond the arts and into other areas of life as well. She frequented Soho loft parties, the Mudd Club, CBGB’s, and Max’s Kansas City — places where artists, rock stars and underground icons mixed and mingled freely. The libertine spirit of innovation and experimentation fuelled a new era in art, one that has achieved mythic status. “We collaborated on projects and experimented outside of our discipline,” Marcia says. “Writers became artists. Artists became filmmakers. Actors became dancers. Everyone was helping each other.”

But inspiration could also come from unfortunate events. One day in 1975, while driving her Ford station wagon through the West Village, Marcia got into a terrible car accident and saw her life flash before her very eyes. Just 24, she lay in the hospital trying to make sense of it all, looking back at what it meant to be a young girl coming of age in America during the 1950s and 60s before the Women’s Liberation Movement and Sexual Revolution.

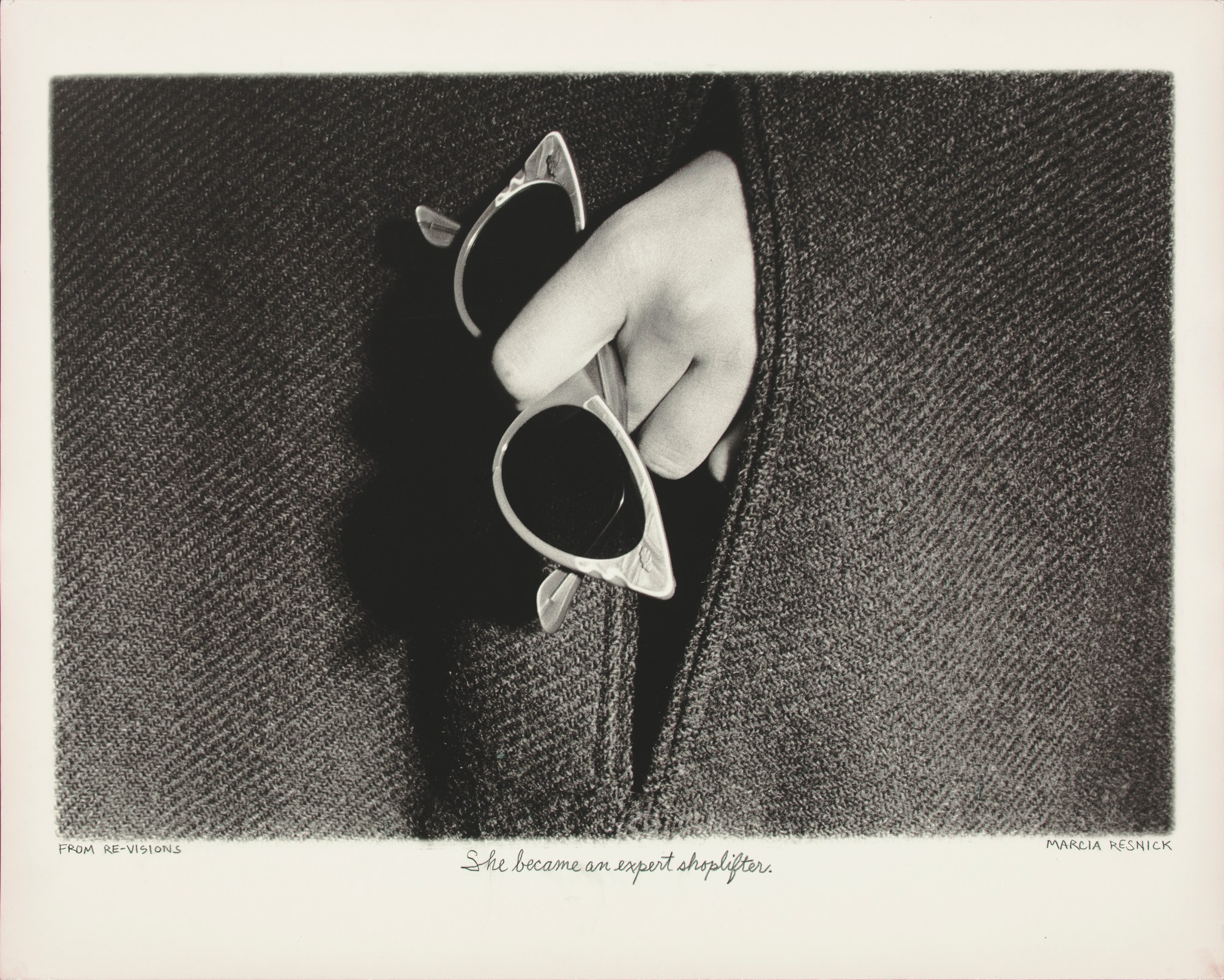

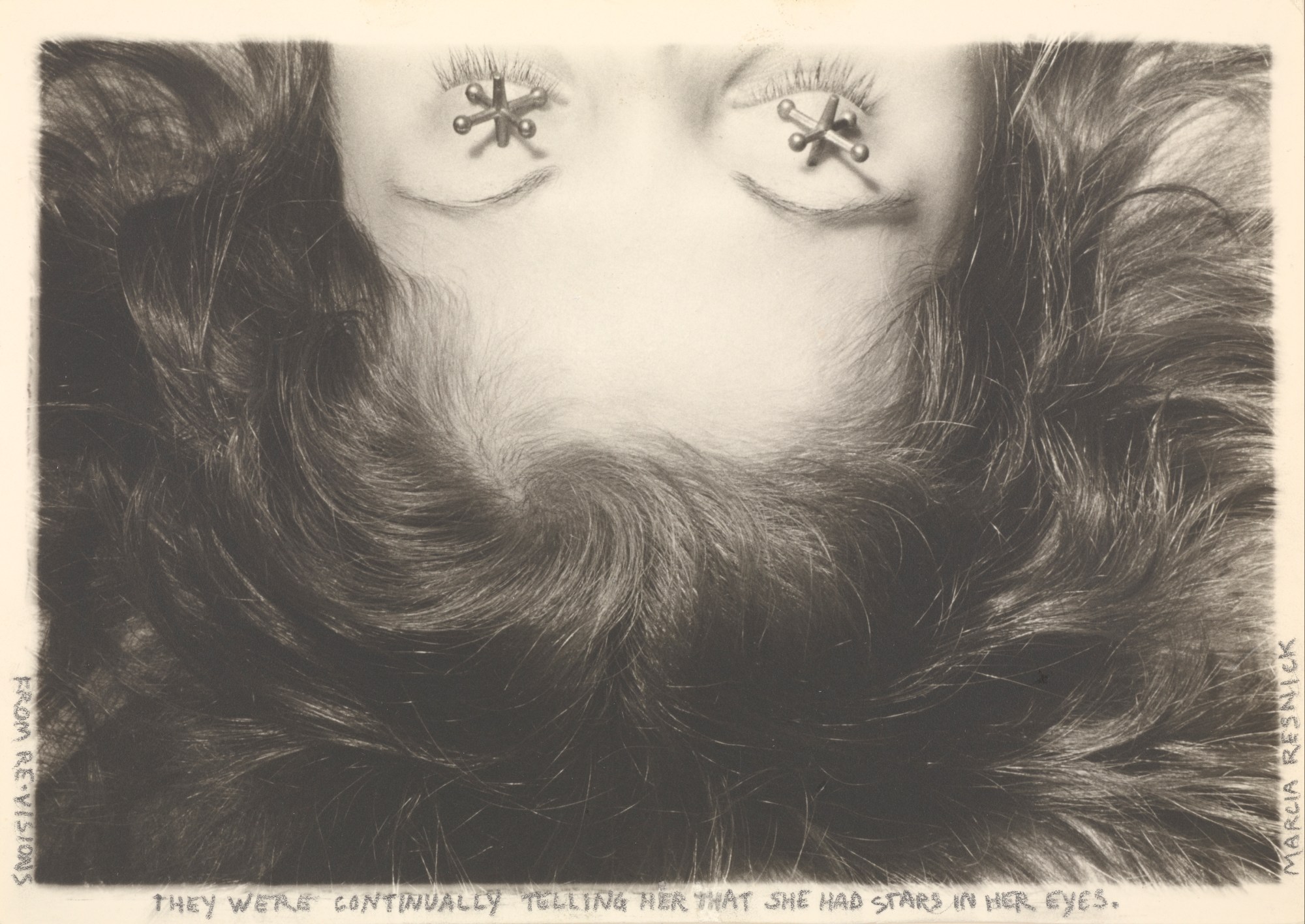

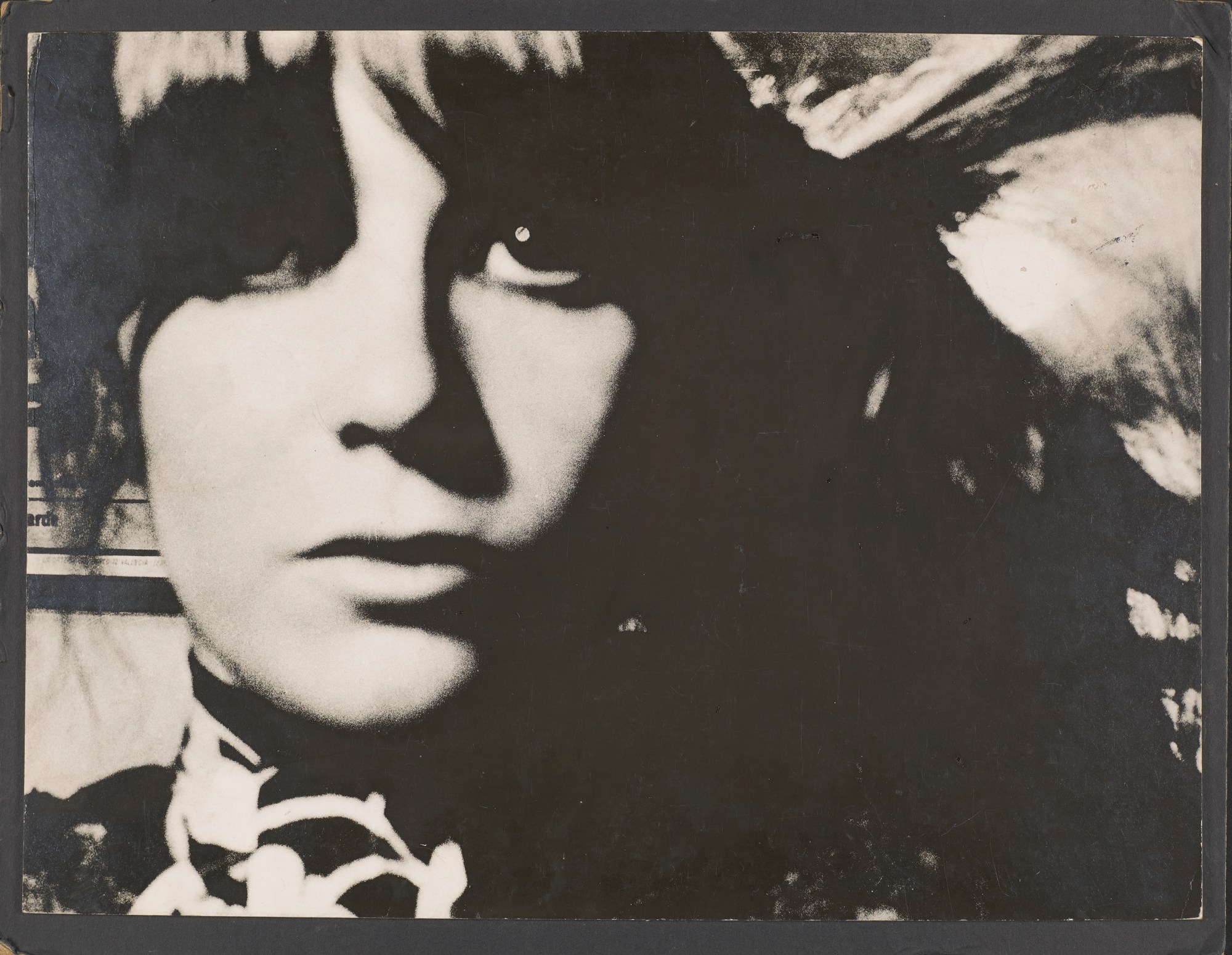

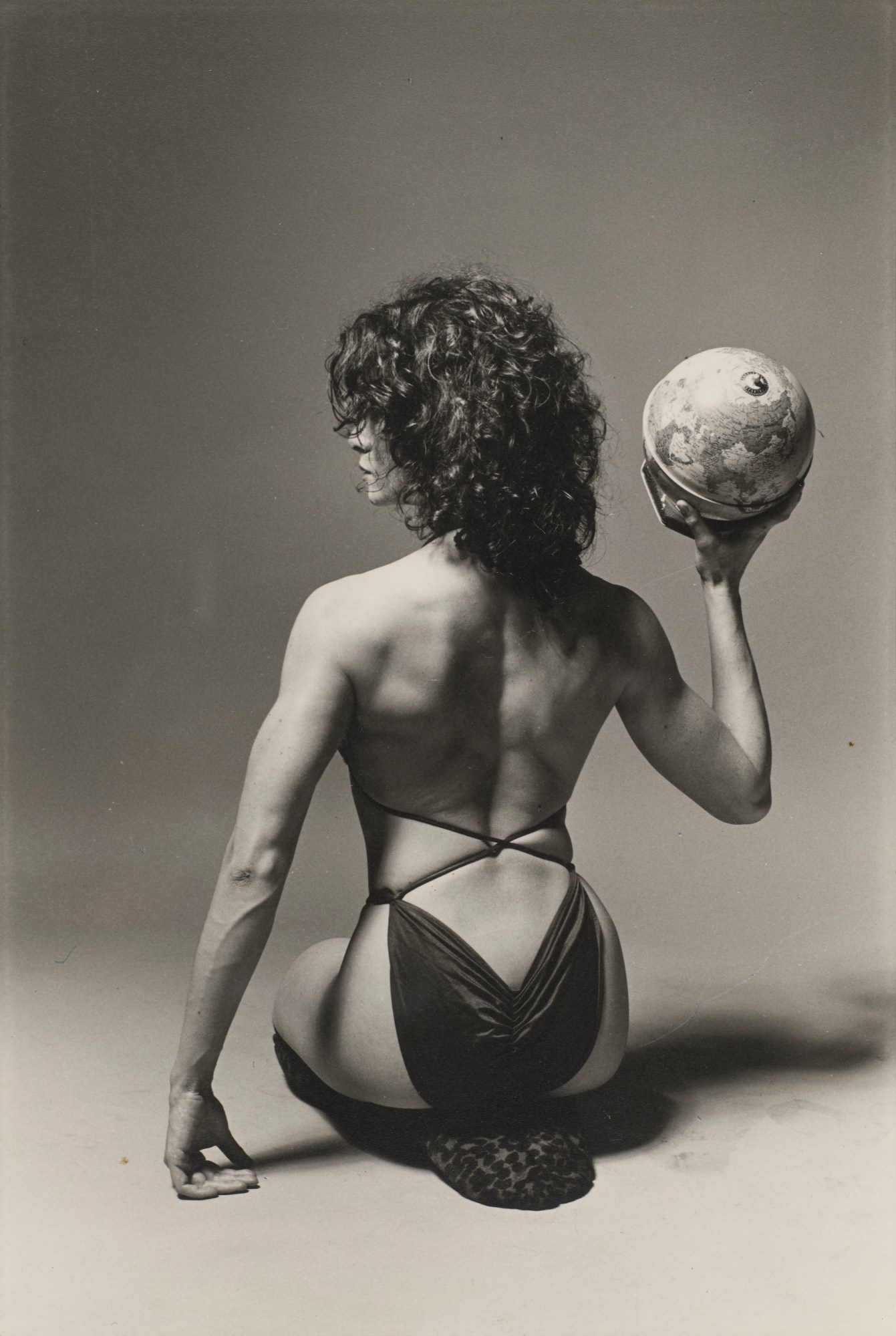

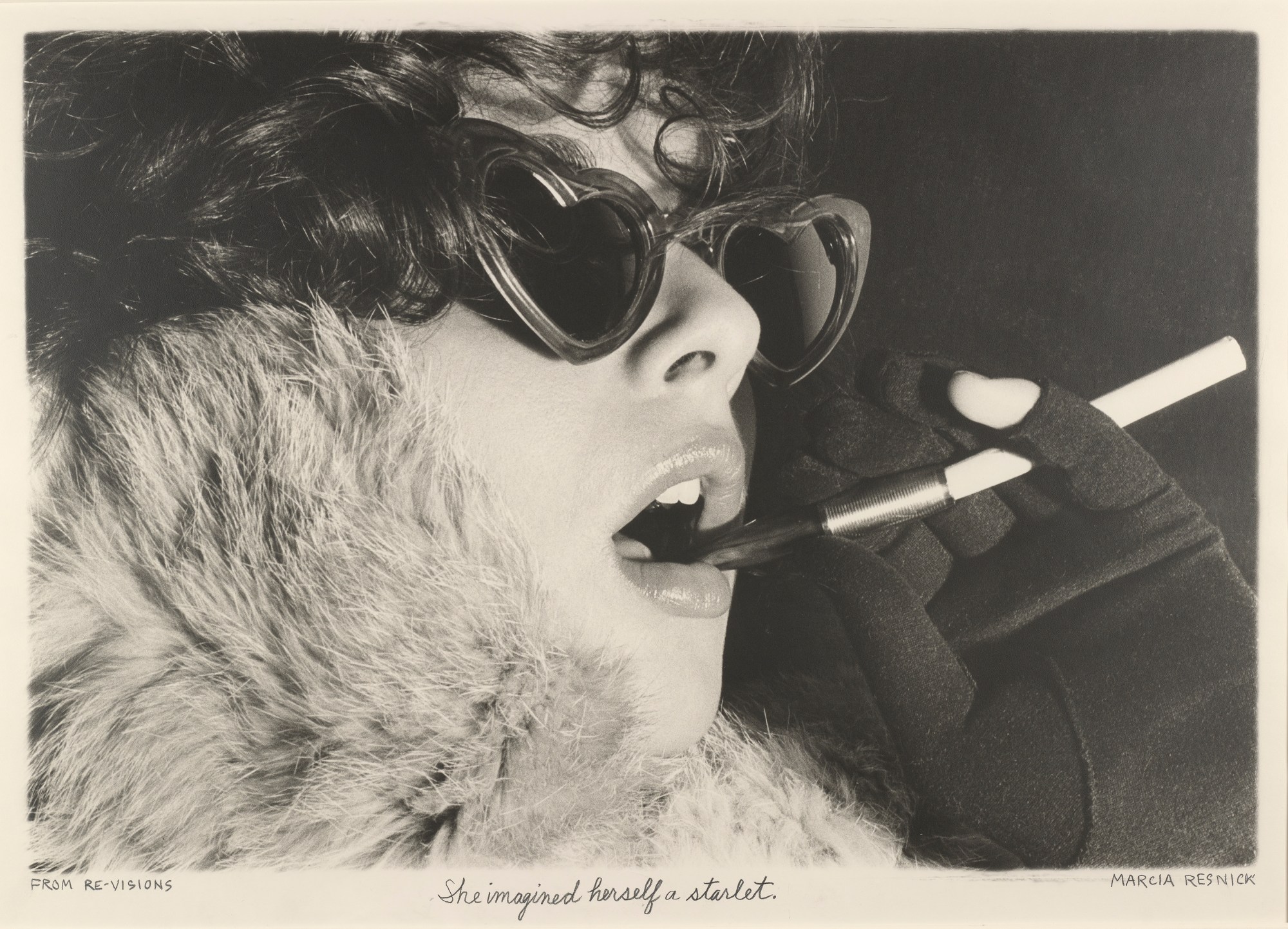

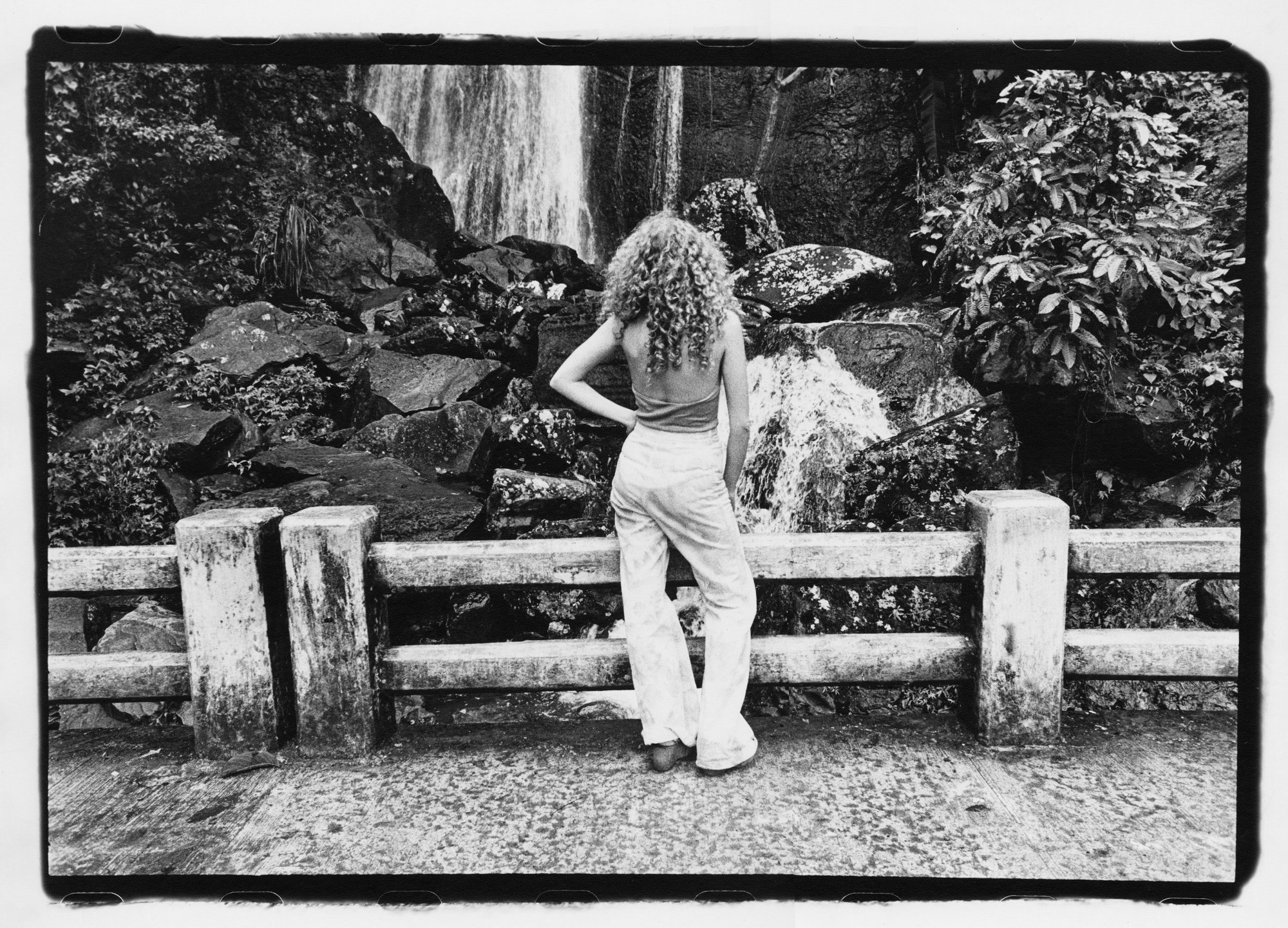

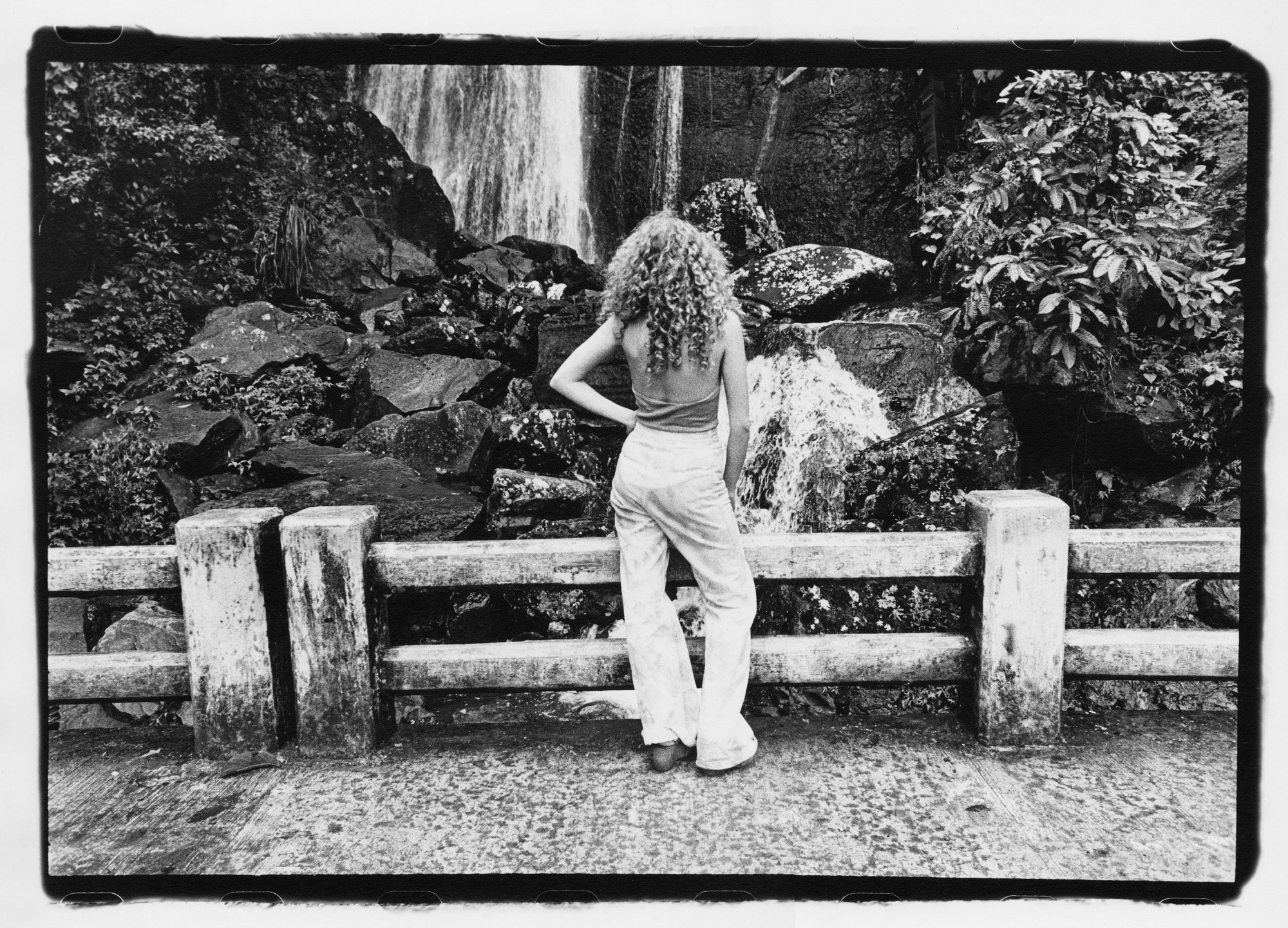

Marcia began writing ideas and drawing pictures for what would become her book, Re-visions (first published in 1978 by The Coach House Press in Toronto and recently republished by Edition Patrick Frey), a poignant, pithy, revelatory visual memoir that William S. Burroughs deemed, “the essence of adolescence”. In it, she staged largely faceless scenes of a young girl coming of age, searching for identity, bound to and rebelling against prescribed notions of gender, sexuality, class, race, ethnicity, and morality.

Using photography to stage scenes that navigate the awkward space between child and adulthood, Marcia saw the potential to become the narrator of her own story. In the photo book, she discovered an authoritative voice that could help her make sense of life’s mystery, majesty and messiness.

With Re-visions, Marcia had reached a deeper understanding of herself and her inner life and decided the time had come to move away from conceptual art. As she decided to explore the world outside of herself by beginning to make portraits, Marcia then got closer to a subject that had always perplexed and confounded her: the male species. She would meet people who intrigued her at clubs and invited them to her studio to be photographed.

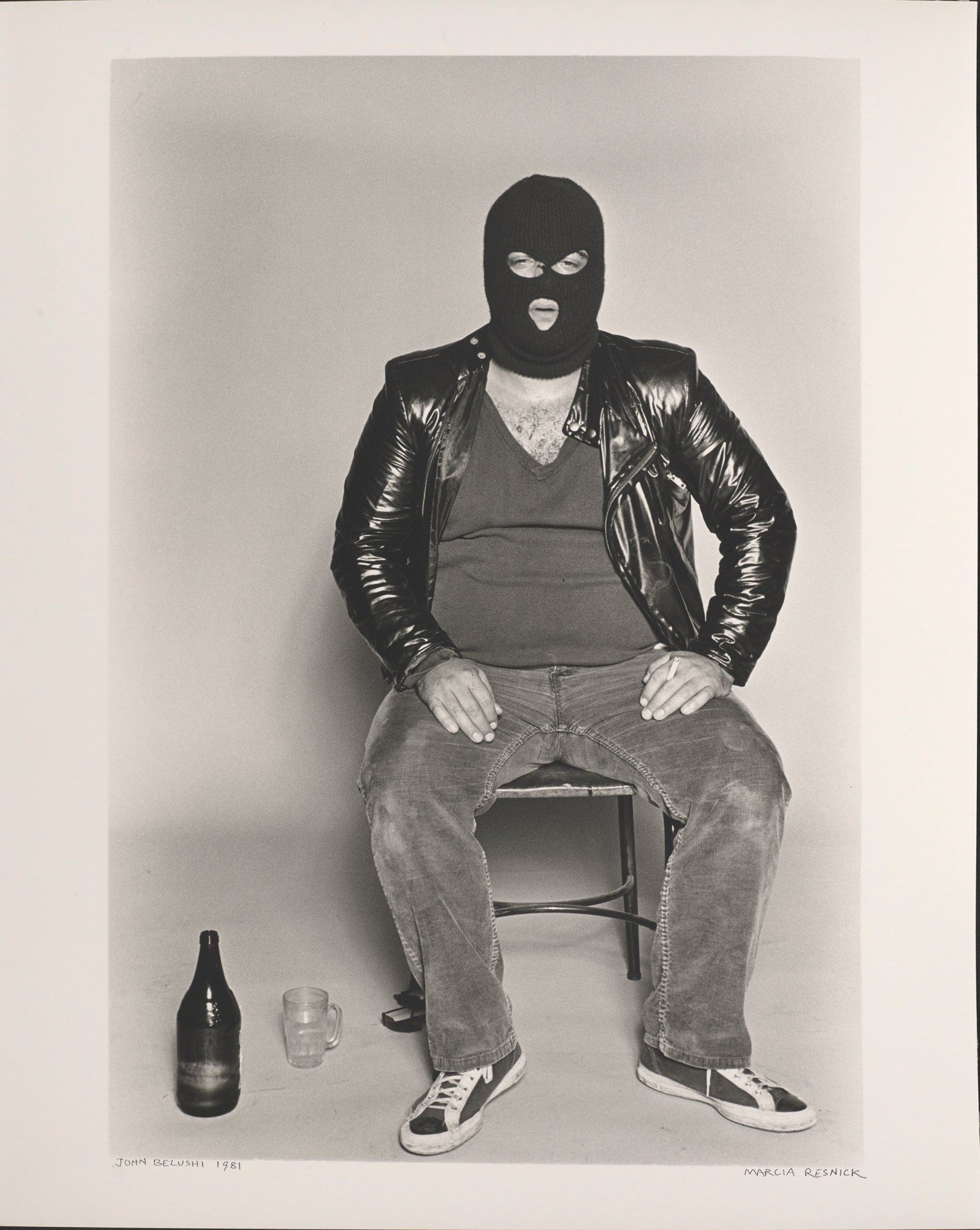

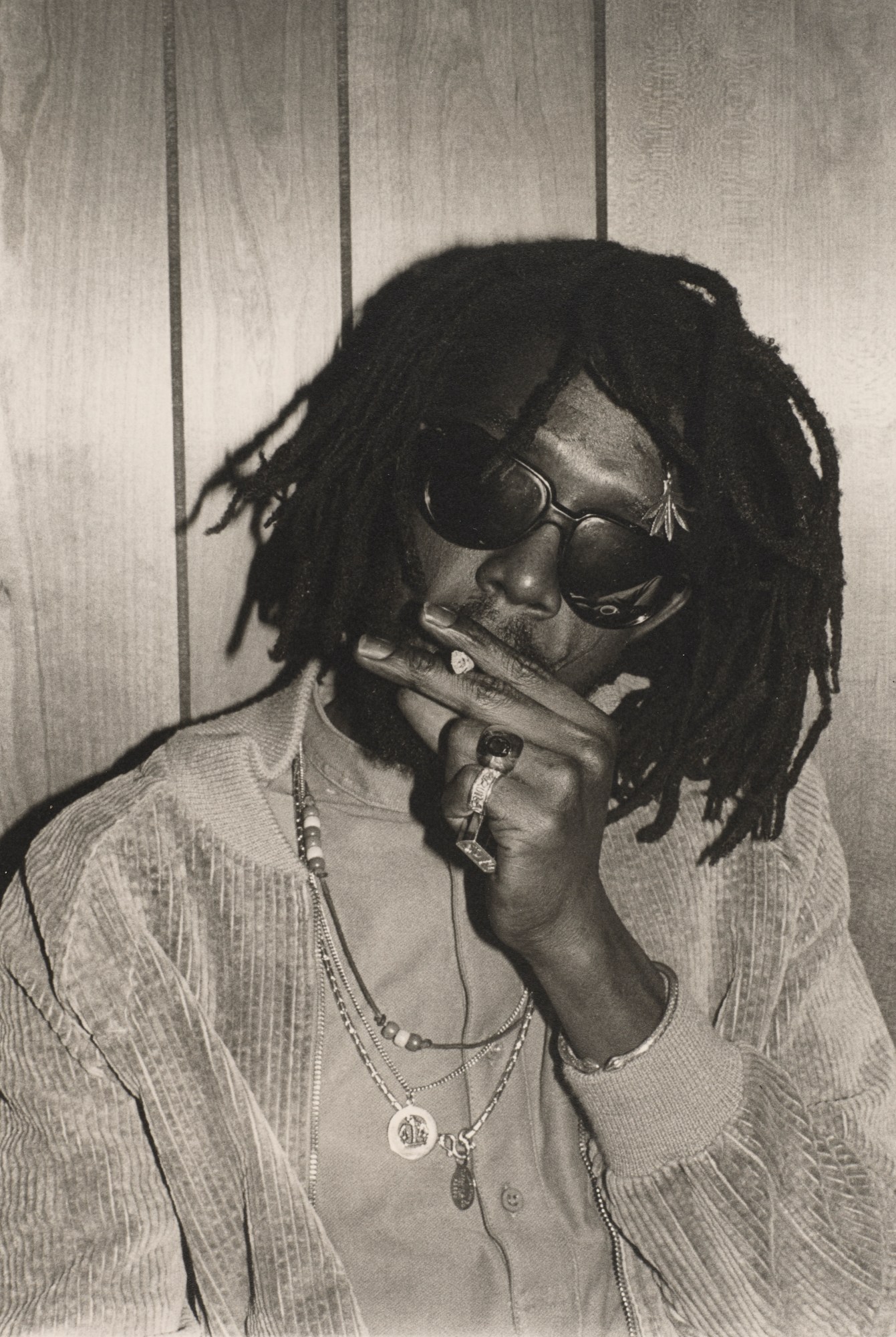

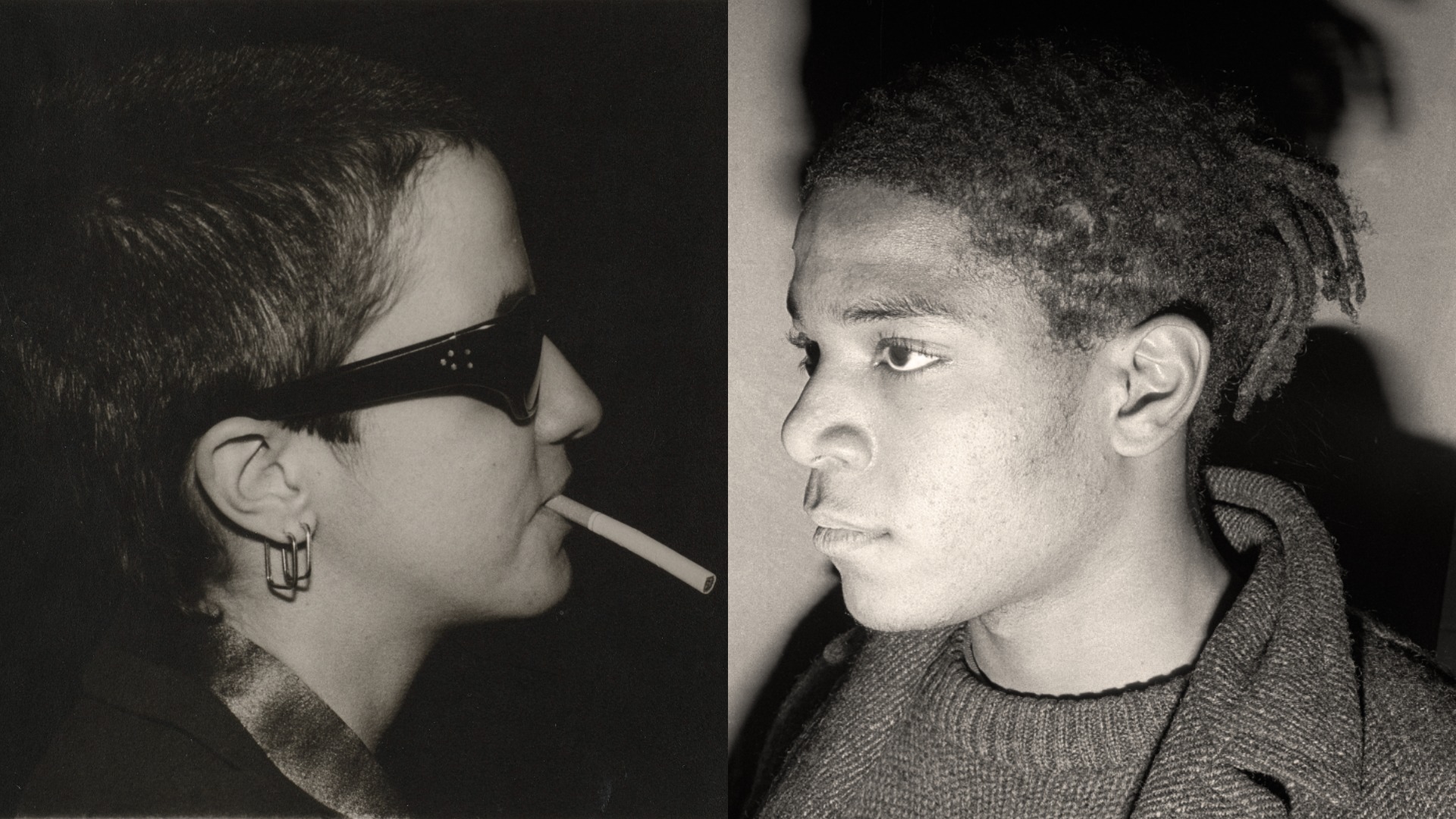

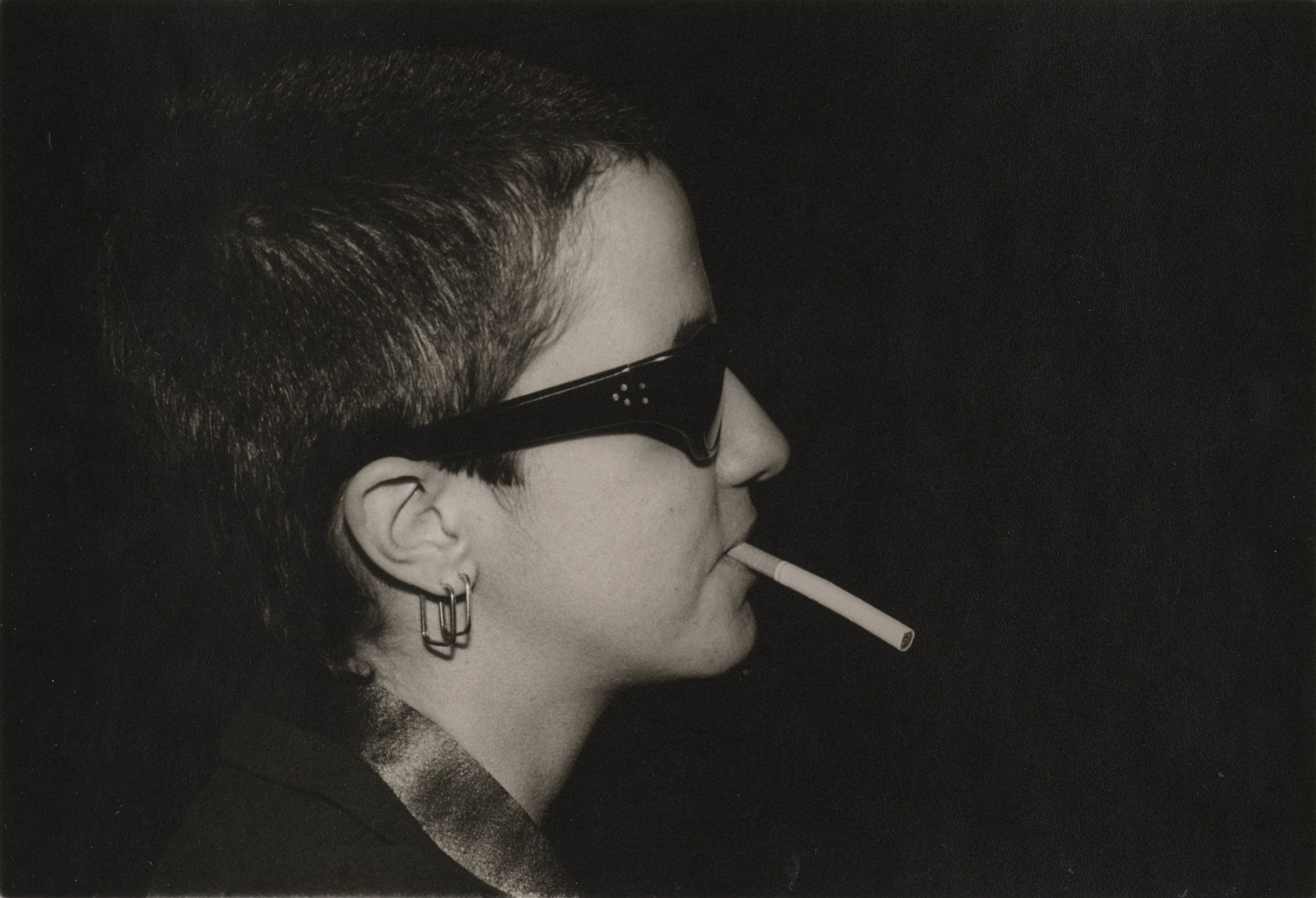

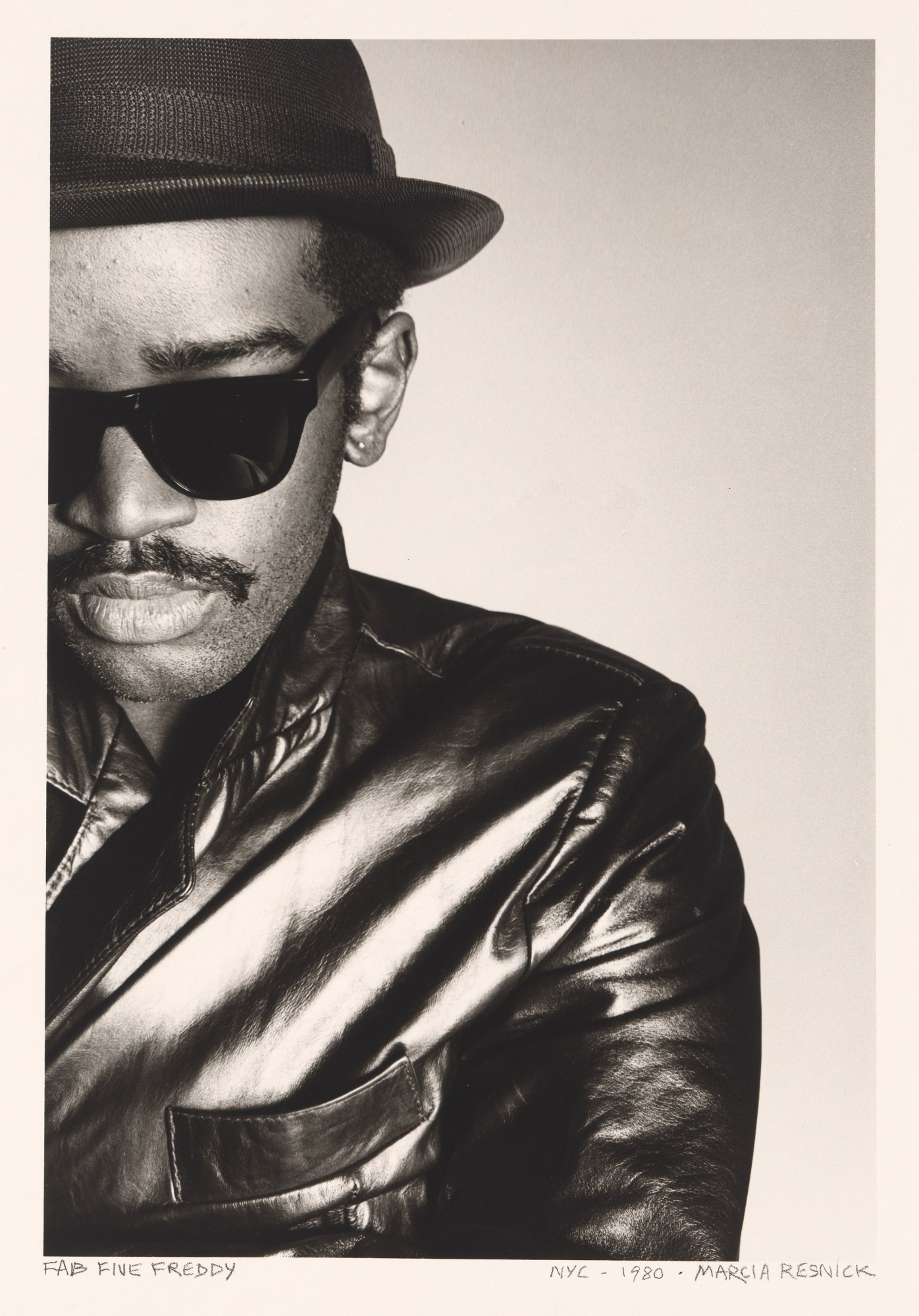

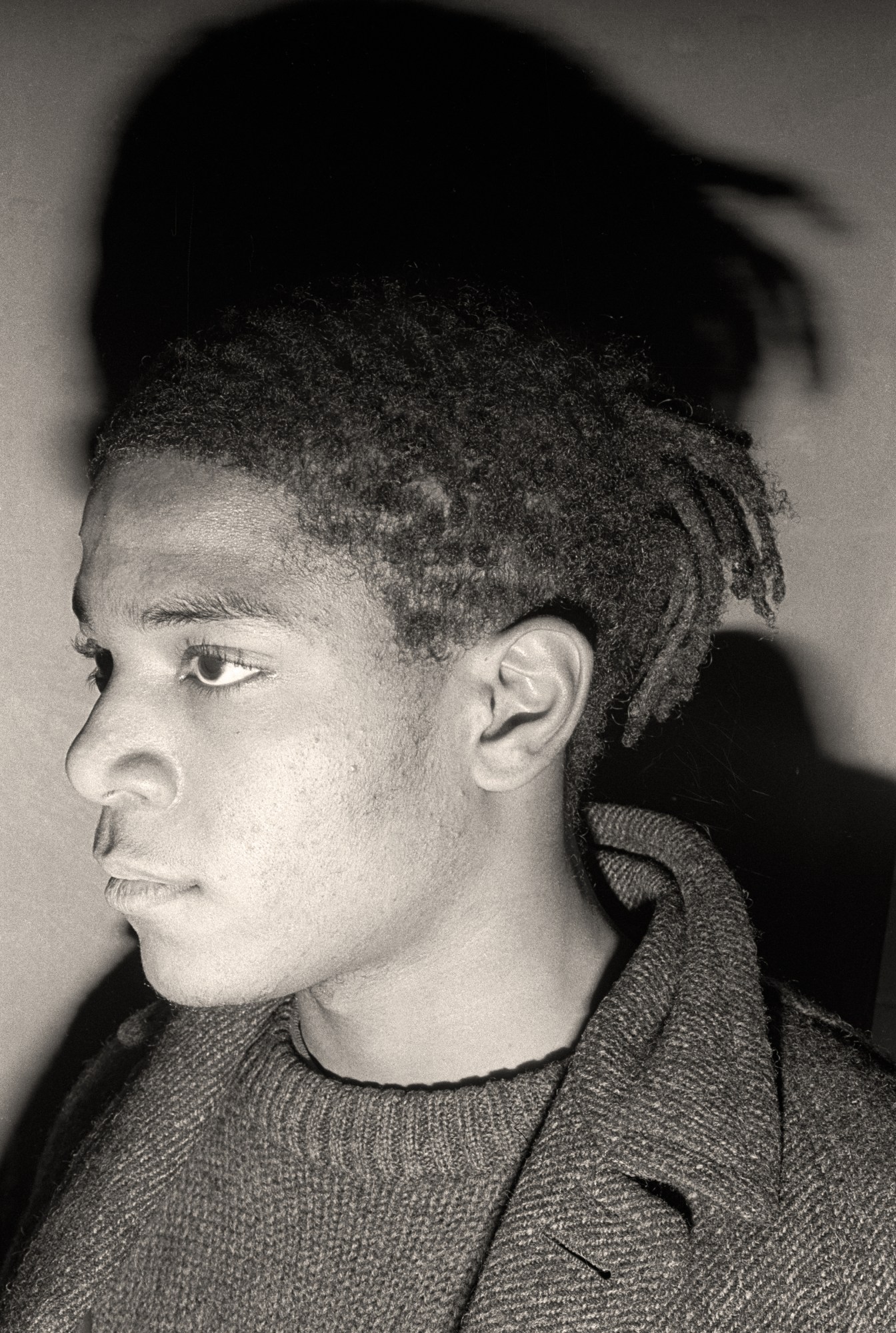

Seeking out radicals who embodied the spirit of the times, Marcia embarked on the Bad Boys series, later published as Punks, Poets & Provocateurs, a collection of captivating portraits of some of the most influential men of the era. From 1977 to 1982, Marcia arranged sittings with luminaries and iconoclasts alike, people who had one thing in common: a DGAF attitude. From Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, and Allen Ginsberg to John Belushi, John Waters, and Divine; Marcia’s portraits capture the formidable and vulnerable sides of the era’s counterculture icons.

“Most of the people I selected both enjoyed being photographed and exuded a certain charisma,” Marcia says, describing how she quickly discovered that she could subliminally elicit a response without saying a word. “I found myself posing on my side of the lens, and I think my movements provoked certain unconscious, automatic reactions. A give and take occurred on both sides, resulting in an esoteric yet productive exchange.”

Despite her efforts, Marcia reveals, “I came out the other end not knowing any more or any less about the opposite sex. The divide between men and women would remain my own exotic mystery.” But she remained resolute, creating the complementary series, Wild Women, to showcase the women who carved a space for themselves in the largely male-dominated punk scene, photographing rock stars like Debbie Harry, Joan Jett and Lydia Lunch.

Although Marcia’s work was not widely embraced by the male-dominated art world or the emerging feminist art movement of the time, she created a way to negotiate the world on her own terms. And today, half a century later, the world is finally catching up to the innovative mind of the original Wild Woman from Brooklyn.

Marcia Resnick: As It Is Or Could Be is now on view at Bowdoin College Museum of Art through June 5, 2022), and will be traveling to Minneapolis Institute of Art (August 13 through December 11, 2022) and the George Eastman Museum (February 10 through June 18, 2023).