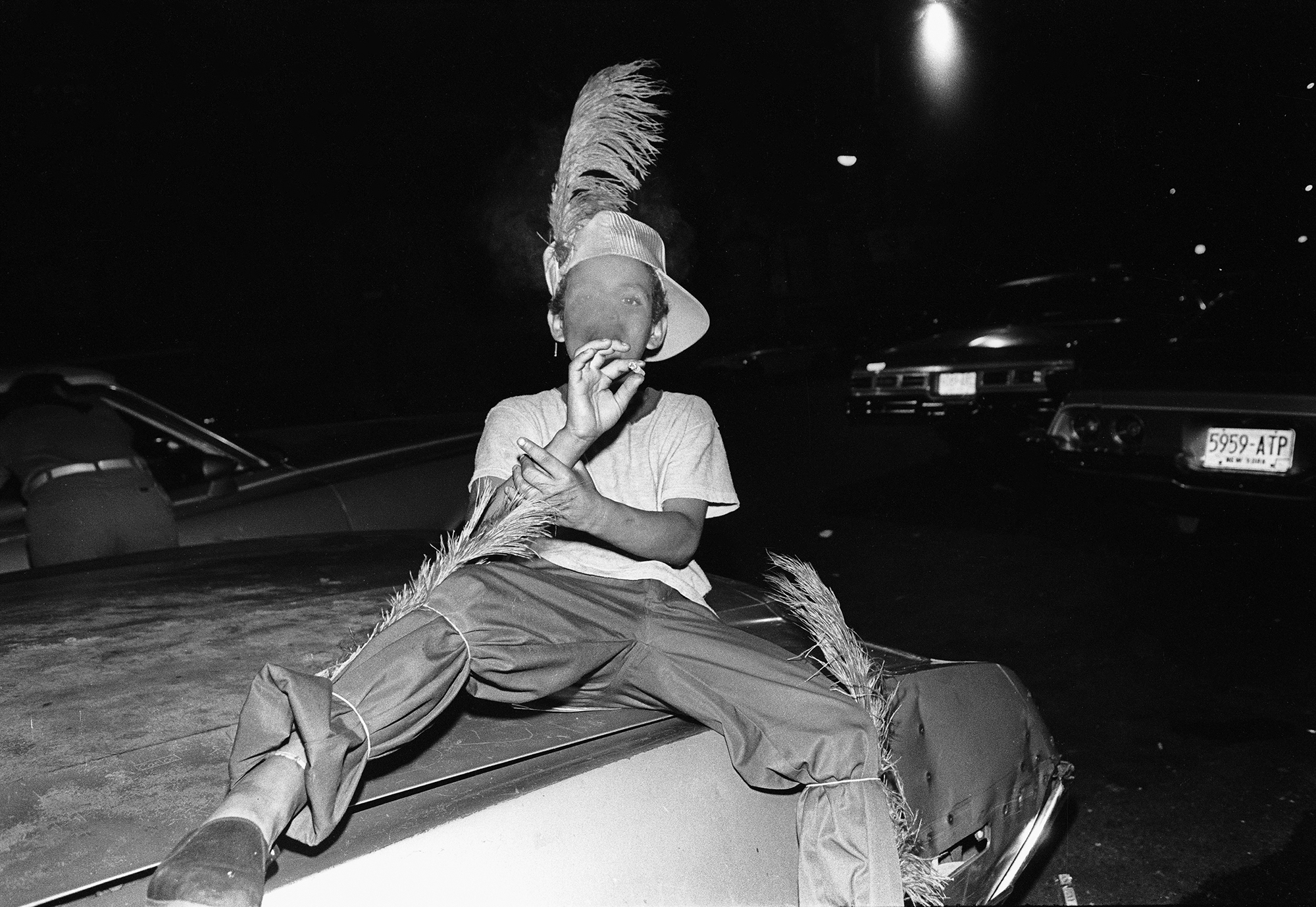

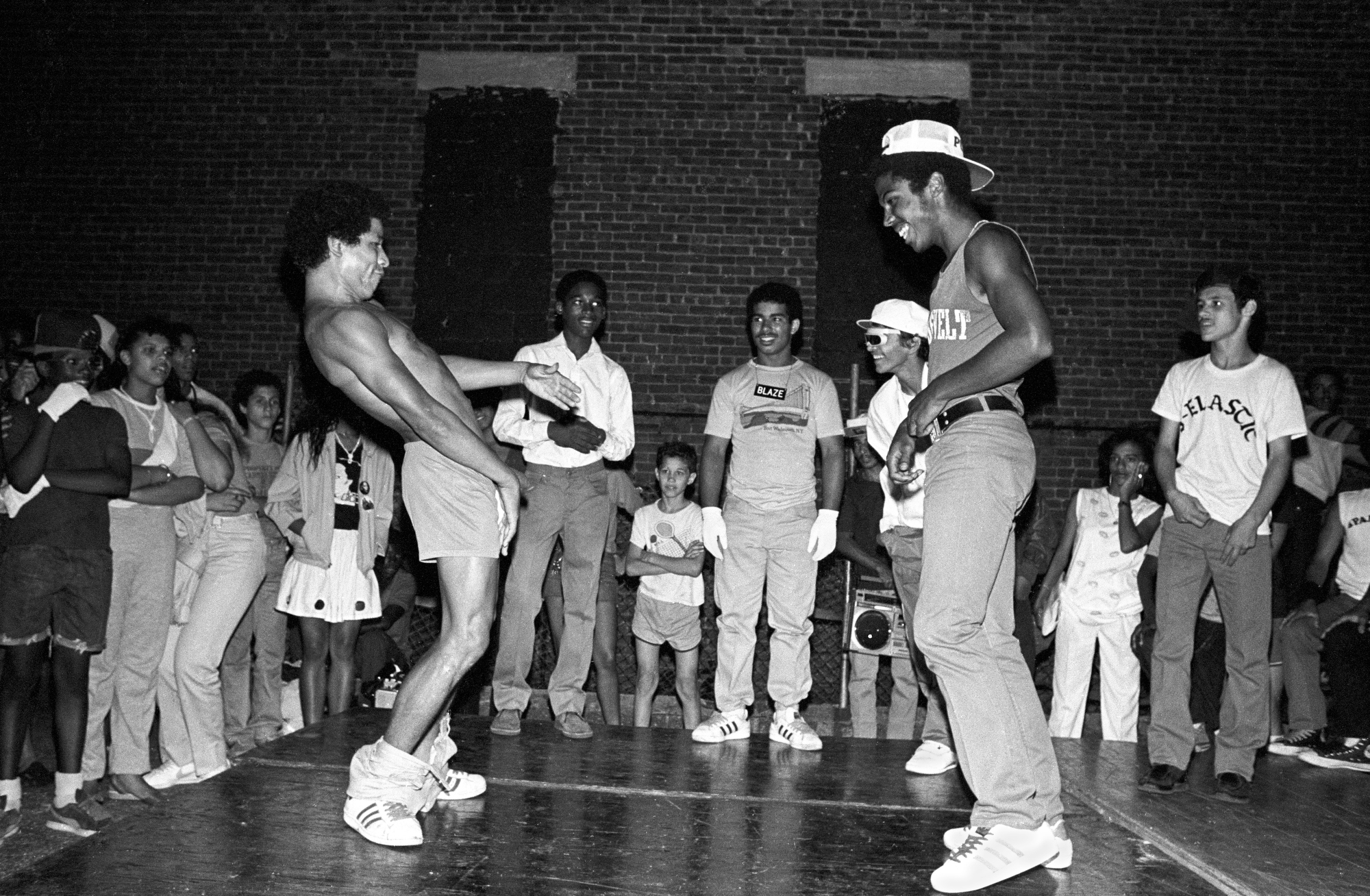

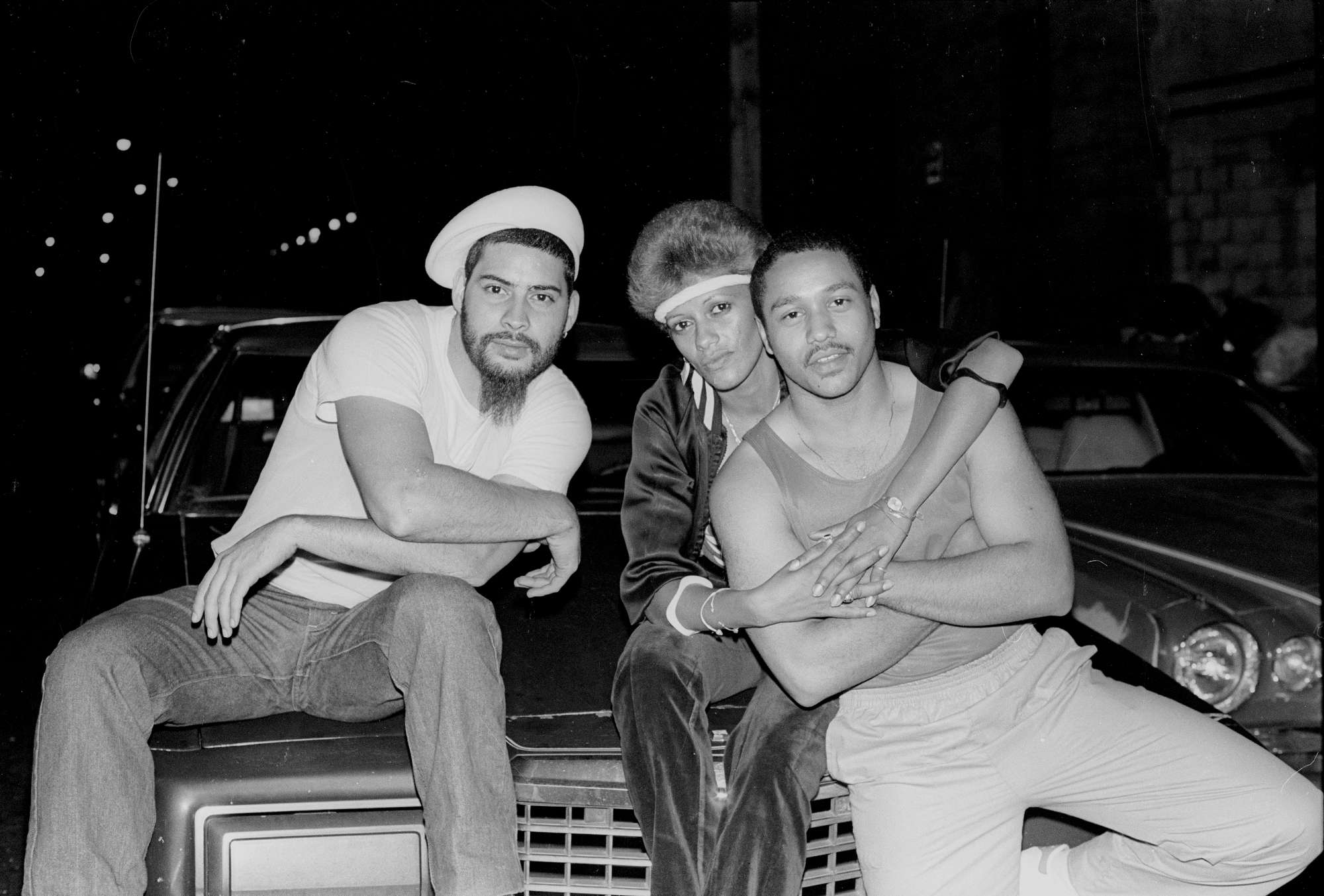

“Rap is now a billion-dollar industry that has had [an] impact worldwide — but what doesn’t get talked about is why poor and working-class communities gravitate to this culture and why it continues to reverberate nearly 50 years later,” says Puerto Rican photographer Ricky Flores.

Growing up in the Longwood section of the South Bronx during the 1960s and 70s, Ricky bore witness to the destruction of his once-flourishing community just as hip-hop rose from its streets. Landlords, realising they would make more money collecting insurance rather than rent, set fire to their properties. By the early 80s, 80% of housing was lost to fires in the South Bronx, reducing the neighbourhood into blocks of rubble that resembled a war zone.

“You can go on YouTube and see in some places where they have no paved roads, and people are dancing on the streets barefoot,” Ricky says. “For a lot of people, graffiti was a big fuck you — you don’t care about us, and we don’t care about your fucking train. The culture was and still is used as a weapon to point out dissatisfaction with the cultural and political situation no matter where people are. Hip hop is an easily adaptable tool for people who are struggling and fighting for change, as well as a way of reaffirming our identity. Hip hop was created under conditions that took place in the South Bronx, but that was also happening in Black and Latino communities nationwide. We grew up in this, and that shit is not glamorous. It ain’t sexy. It’s fucking appalling.”

The story of the Bronx runs parallel to that of the north-east corner of the US. Once Lenape lands, the British colonised it in the 17th century, transforming the highlands into farmlands owned by the aristocratic family of Founding Fathers Gouveneur Morris and Lewis Morris. After New York City annexed the Bronx in 1895, it became a bustling centre for newly arriving Jewish, Italian, Irish, and German immigrants. During the Great Migration of the 20th century, waves of Black Americans arrived from the South, seeking reprieve from Jim Crow, only to discover the horrors of de facto segregation.

Puerto Ricans decamped for the mainland during World War II when the United States implemented Operation Bootstrap in an effort to rapidly industrialise the colonised island. “We are trying to lift ourselves by our own bootstraps,” Puerto Rico’s first elected governor Luis Muñoz Marín told Congress in 1949, seemingly unaware that the expression was originally a form of ridicule describing an impossible act. While the government sought foreign investments to create low-wage, labour-intensive factory work in PR, hundreds of thousands took flight, migrating to the United States between 1940 and 1970.

Ricky’s family were among early arrivals to the Bronx. His father, a Merchant Marine, died when Ricky was just five, while his mother worked in the Garment District as a seamstress until mental illness began to manifest in the late 1960s and early 70s. After his father passed, the family moved into a building where he would spend his formative years just as ‘white flight’ began: in the 1970s alone, every one in five residents left for the suburbs.

“The community was very vibrant and alive, the streets completely packed with kids playing and people living their lives. Everybody knew each other and looked out for one another. There was a strong sense of community,” Ricky says. “Then, in the late 1960s, the first wave of heroin addiction began. Young men in the neighbourhood served in Vietnam and brought that back with them. It spread like wildfire from 1966 to 1973. You would see them nodding on the corner. For a young kid like myself, it was a horrifying experience.”

Then the fires began, destroying the community block by block as the decade wore on. “It was gradual,” Ricky says. “The landlord would stop providing services to the building, but they still tried to collect rent. We became stronger, and it became dangerous for them to come. Eventually, they stopped coming, and that left us with a problem: there were no services to our building, and no feeling of what would happen next.”

Aware of the destruction happening throughout the neighbourhood, Ricky recalls a visceral fear that created a prolonged state of hyper-vigilance that ultimately resulted in PTSD. “We developed this sense of protection for our buildings,” he says. “If we smelled smoke coming from an apartment, we would raise hell on that door. I actually broke some poor guy’s door because he was drunk and fell asleep while some food was burning on the stove. That’s a sick thing to think about — when you’re a teenager and your skillset is breaking into people’s apartments to stop a fire. Particularly in those days because there were four or five locks and a security bar — to get into someone’s house was a fight.”

Being in a constant state of high alert, Ricky became a light sleeper, always attuned to the sound of fire trucks approaching the building. “They didn’t always run with sirens,” he says. “They could just come in quietly on a call. I would hear the throbbing of the engine and be instantly awake. I lived like that for years. It was only after I moved up to Westchester that I started to grow out of it. We talk about post-traumatic stress disorder as it relates to the military and the fact is we live in those very conditions as poor and working-class communities regardless of colour. People live under stress year after year after year, and the impact is generational.”

With all his senses attuned to the environment, Ricky recalls moments where he would be standing on the corner with a group of friends on a beautiful day, only to notice a subtle change in the air. “You knew something was about to go down but you couldn’t figure out where,” he says. “Sure enough, something would pop — I can’t even explain it. Those skills became extremely useful to me as a photojournalist covering confrontations between the community and the police.”

By the 1970s, Longwood’s 41st Precinct of the NYPD dubbed itself “Fort Apache“, aligning itself with the 1948 Western that cast John Wayne and Henry Fonda in a battle for white supremacy over the Apache of Arizona. At a time when gangs like the Savage Skulls, Black Spades, and Spanish Mafia took to the streets, police officers saw themselves as “good guys” keeping order in a lawless land. Local officers like Ralph Friedman describe their time at the 41st with aplomb: “I started going out looking for trouble. I’d feel lucky to find it… Back then, I loved making arrests: The adrenaline was like a drug. I was like a kid in a candy store.”

In 1976, NYPD Captain Tom Walker published Fort Apache: New York’s Most Violent Precinct, a searing chronicle of his time at the 41st Precinct. Hollywood, already fully enthralled with New York-set neo-realist copaganda films, came calling. Paul Newman, Pam Grier, and Danny Aiello began filming the 1981 movie Fort Apache, The Bronx, painting a lurid portrait of the South Bronx filled with gang members, junkies, sex workers, and psychopaths — much to the community’s outrage. Activist Dr. Evelina Antonetty, affectionately known as “The Hell Lady of the Bronx,” organised protests that shut down filming and threatened to file suit — resulting in a disclaimer that ran at the beginning of the movie stating, “This movie does not portray not portray Latinos and blacks of the Bronx accurately…”

Counter-narratives were in short supply. Fortunately, Ricky, who took up photography in 1980 during his senior year of high school, began creating a visual diary of his life in the South Bronx. What began as a hobby soon became his life’s work after studying with Mel Rosenthal, one of the most significant chroniclers of the area. While the media sent outsiders in to produce sensationalised new stories, Ricky created a singular archive of street life, documenting the people who lived by the Bronx’s motto: Ne cede malis (Do not yield to evil).

“There was a growing realisation on my part that the South Bronx was connected to what was happening citywide between communities and the police department,” Ricky says. “School programs were getting cut. Landlords were abandoning tenants. Living conditions were poor. My community was selectively decimated. In the middle of that was me, a young Puerto Rican man becoming more politically active — while we were developing this culture, hip hop. This is what we grew from, and what it actually felt and looked like.”

Credits

All images courtesy Ricky Flores