Romance books have always been popular, but never before have people been so vocal about enjoying them. “I have readers of all ages, and especially older ones, who say they started reading the genre when they found books that their mothers or grandmothers had hidden under the bed,” Talia Hibbert, author of the acclaimed series The Brown Sisters, tells me. “It was kind of a secret affair. The main difference now is that we’ve reached a point where it doesn’t need to be.” The period since the pandemic began has seen sales of romance fiction soar by 49%, but they were high to begin with. Rather than increased sales, however, the biggest shift has taken place on social media, where communities of young fans have blossomed.

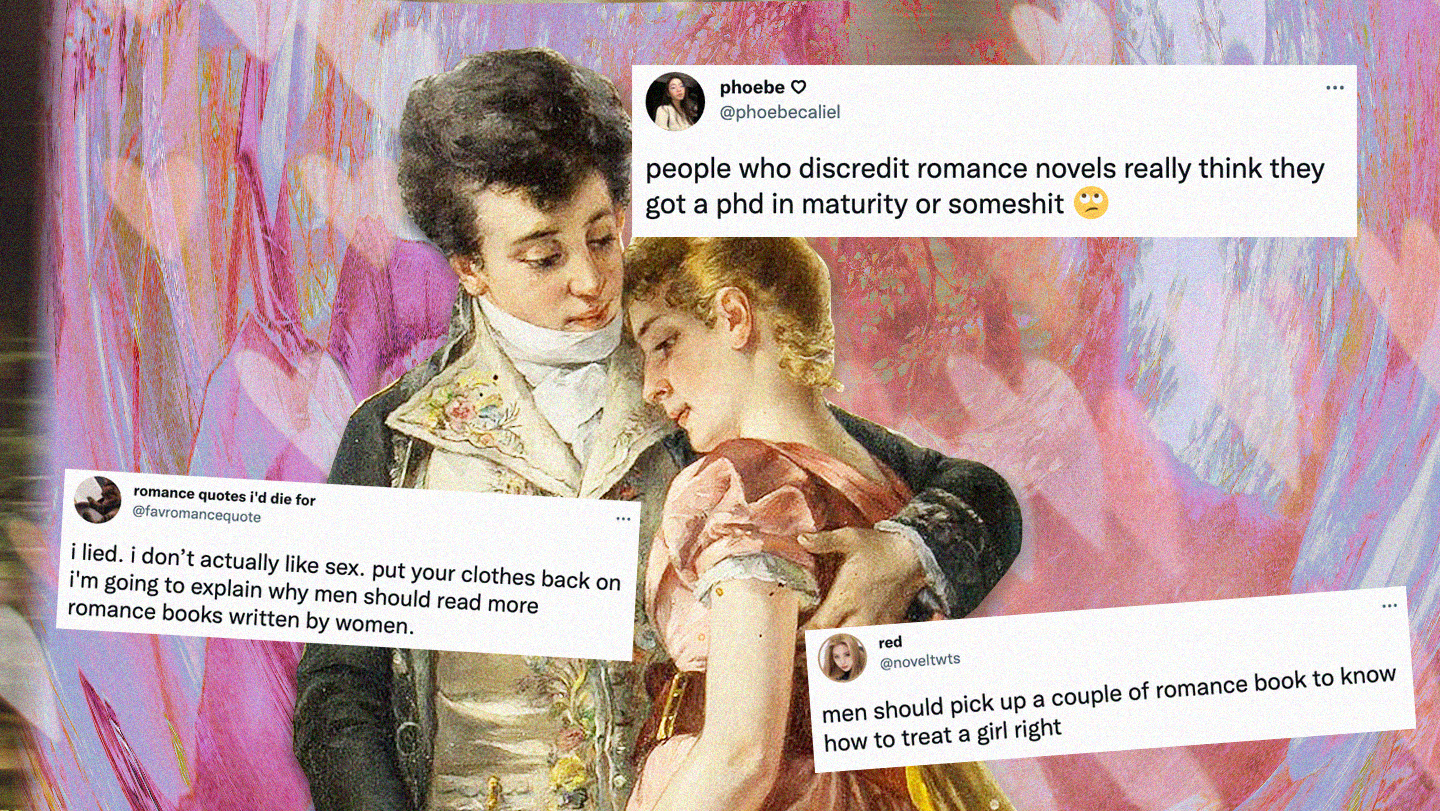

Every single day on Twitter, I come across a viral tweet about romance — often people complaining that it’s unfairly ignored as a genre, or else wishing that men in real life behaved more like the heroes of their favourite books.

The genre has become a mainstay on ‘BookTok’ too, a space publishing houses and retailers are using as a key marketing tool in 2022. “It’s an accessible platform where people are able to get book recommendations in the blink of an eye,” 22 year old Lauryn Hickman, who TikToks about fiction to her 300k followers says. “Primarily, we are recommending romance.”

Despite becoming a bonafide cultural phenomenon on social media, romance remains under-discussed in the mainstream. “Overall, I think genre fiction is always represented negatively compared to literary fiction, and within genre fiction, there is a hierarchy — romance does tend to be right at the bottom,” Talia says. “I think that’s because in a patriarchal society that prioritises the idea that feelings are gross and embarrassing and stupid, a genre that’s entirely about feelings is always going to be looked down on.” This seems true: people mock the rigid formula which dictates that romance books must have a ‘Happy Ever After’ or ‘Happy for Now (HFN)’ ending, but it’s rare to see people make fun of detective novels for eventually revealing the culprit.

It’s difficult to see why romance would be more deserving of scorn than crime, horror, sci-fi or fantasy, yet this kind of sneering is common — the fact that it’s primarily read and authored by women is surely not coincidental. “A lot of people see romance as somewhat a less respectable genre because it seems ‘silly’ or ‘cheesy’,” Lauryn says. “Some people say that romance doesn’t really hold deep messages or themes in the same way that literary fiction does, or that it doesn’t have the same depth as high fantasy books.” While men, both gay and straight, do read romance, it’s still a genre primarily consumed by women, which can inspire a certain misogyny-tinged snootiness: in 2017, literary critic Robert Gottlieb faced a backlash for writing in the New York Times, “Its readership is vast, its satisfactions apparently limitless, its profitability incontestable. And its effect? Harmless, I would imagine. Why shouldn’t women dream?”

For Talia, the fact that romance has historically been disrespected might itself be a source of appeal for younger readers. “Reading romance might feel subversive because of how it’s looked down on, because of how we’ve all been taught that emotions and love and happiness are silly. To take an unashamed pleasure in reading romance is a challenge to all that.” As Talia sees it, Gen Z are generally more conscious of unfairness and social justice than the generations before them, partly as a result of being so online. This could go some way towards explaining why the genre is becoming more diverse, even if there is still work to be done. The progress which has been made is the outcome of a long struggle for greater diversity within a genre which has long had problems with racism (although by no means uniquely). Even today, Mills and Boon, one of the largest distributors of romance fiction, still publishes books with titles like Bound by the Sultan’s Baby and Bound to Her Desert Captor (curiously, titles about Sheiks became more popular after 9/11). Crucially, though, these aren’t the books young people are raving about on TikTok.

Something interesting about the popularity of romance today is that it’s taking place within the context of a popular culture which isn’t very romantic at all. While rom-coms have found a home on streaming platforms, the genre has all but disappeared from mainstream Hollywood, along with gross-out comedies about sex. The major franchises – namely Marvel and Star Wars – are not especially concerned with romantic love, and they’re definitely not interested in sex: as film critic R.S Benedict put it, in these films “everyone is beautiful. And yet, no one is horny.” Echoing this point, Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar said in 2019, “sexuality doesn’t exist for superheroes. They are neutered.” The sex scene has been in decline for a long time, which is less due to cultural prudishness and more to do with vulgar economics: mid-budget films for adults have largely been abandoned in favour of expensive blockbusters which need to cater to all age groups in order to be profitable. TV has picked up the slack to an extent (Netflix’s Bridgerton, a big hit, is based on a series of romance novels), but there is nonetheless a dearth of romantic and erotic love within mainstream culture. For lots of people, this is a gap being filled by romance books. ”If you are someone who has felt underserved by the recent trends in the last decade or so in film,” says Tilia, “then maybe you are going to reach a point where you realise that you want to see people falling in love and having a good time. Since you’re struggling to find it elsewhere, you’re pushed to reading about it.”

This deficit of romance is not just limited to popular culture. Year after year there’s a surfeit of articles about how people are having less sex or staying single for longer. Birth and marriage rates, the typical ‘Happy Ever After’ stuff, are both in decline. The pandemic has exacerbated isolation – something which Talia suggests is a factor in romance’s resurgent popularity.

If the fall-out to the West Elm Caleb controversy (in which a man in New York went viral for his poor dating etiquette) suggests anything, it’s that lots of young people are disillusioned with the casual indifference of contemporary dating, the grinding banality of being on the apps. Maybe this is why a good portion of the tweets you see about romance express a sense of yearning about the gap between how dating is portrayed in books and the often disappointing reality. “Romance books typically are a bit unrealistic and the events that happen in them are idealistic,” Lauryn says, “but they could conceivably be real. The characters in the book are real life people with real life jobs, families, and trauma. It makes it feel like perhaps people really could act like this in real life. I definitely think that the popularity could be a response to the way that society is, and to some extent act as an escape.”

Rebecca, a millennial woman who started reading Regency-era Mills and Boon novels during the first lockdown, concurs: “I would probably agree that there is a lack of romance in society and that’s maybe symptomatic of instant gratification or atomisation, or whatever” she says. But the appeal for her is simply that she enjoys them. “For me, the reading experience is basically the same as reading as a child and obviously that’s quite soothing for a formerly gifted child like myself,” she jokes. “During lockdown I’d use them as pacer books to ease myself into reading other things because the act of actually reading them was so easy. It’s not asking you to consider anything apart from the fact that this governess is going to lose her inheritance unless she marries this man she finds terrible.” While Rebecca favours books from the racier end of the spectrum, she’s more interested in the elaborate courtships leading up to sex than the act itself. “I actually don’t like it when they get too modern and graphic,” she says. “The most recent one I read, which I really disliked (which is rare), kept talking about ‘fingering’ and I kept thinking, ‘Please, this is Victorian times, stop saying fingering — you’re ruining it!’ I don’t know why, because they all have graphic sex scenes, but fingering was just a step too far!”

The popularity of romance fiction among younger readers shows that there is an appetite for stories about love and sex, which, relatedly or not, is ill-catered to elsewhere (even if, admittedly, literary fiction is not short of depictions of young women and their relationships). For some readers, like Rebecca, reading romance is purely about enjoyment, but the genre can bear a deeper significance which shouldn’t be discounted. The professional body, the Romance Writers of America, states that: “In a romance, the lovers who risk and struggle for each other and their relationship are rewarded with emotional justice.” According to Talia, whose novel Get a Life, Chloe Brown follows a plus-size Black woman who lives with chronic illness, this means that romance books can be an important form of representation. “Romance makes a statement about who deserves love and who deserves justice.’” she says. “To have a wide array of marginalised characters taking the main roles within a romance challenges our ideas about marginalisation and love.”

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on books and TikTok.