Late on a Saturday afternoon in early May, Carrie Mae Weems is seated at her desk. For hours now, she’s been deep in the thick of a film edit. The moment she answers the phone for our interview, it feels as if she’s just taken a deep breath, coming up for air after being submerged in new work slowly finding its shape. For a brief spell, she will rest.

“A lot has been written about my work,” she says before asking, tenderly: “What is it that you might like to know?”

Nearly a week ago, she’d been honored by Dior at the Brooklyn Museum’s Artist’s Ball. This kind of recognition has only truly, in the past decade or so, begun to catch up to her vital contributions to the art world. In 2013, she was named a MacArthur Fellow and recipient of their Genius grant. The next year, she became the first Black woman to have a retrospective at the Guggenheim. This past March, she won the prestigious Hasselblad Foundation International Award, considered by many to be the Nobel Prize of photography. It affirms “major achievements in the art and photographic community through thought-provoking, emotive bodies of work,” with past recipients including artists like Nan Goldin, Cindy Sherman and Wolfgang Tillmans.

By now, she must be accustomed to the complicated phrase “First Black Woman.” However, in the case of the Hasselblad she is careful to clarify that she is “the first Black person,” to win. “There is a difference,” she says, her words weighted by generations of Black artists whose work has gone ignored and unsung. “The thing that I’m most grateful for is that there are a whole group of young artists who are coming behind me, who are working in extraordinary ways that would’ve been unimaginable even 10 or 15 years ago. I understand what it means to be the first, but not the last.”

As she prepares for her first solo exhibition in the UK – Carrie Mae Weems: Reflections for Now, a retrospective survey of her practice at Barbican Art Gallery – I ask how recognition makes her feel. “I know what it means to work very, very, very, very hard, and diligently. The work is always challenging; it’s always hard. That doesn’t stop. That is the work. Even as I win awards and I’m acknowledged for what I do, the thing that is still the most engaging, the thing that is most exciting, the thing that really gets me up in the morning, is not the recognition, but the discovery and the magic that comes with…” she pauses gracefully to grab hold of the right words. “Delivering on your own promise, that you’ve made to yourself.”

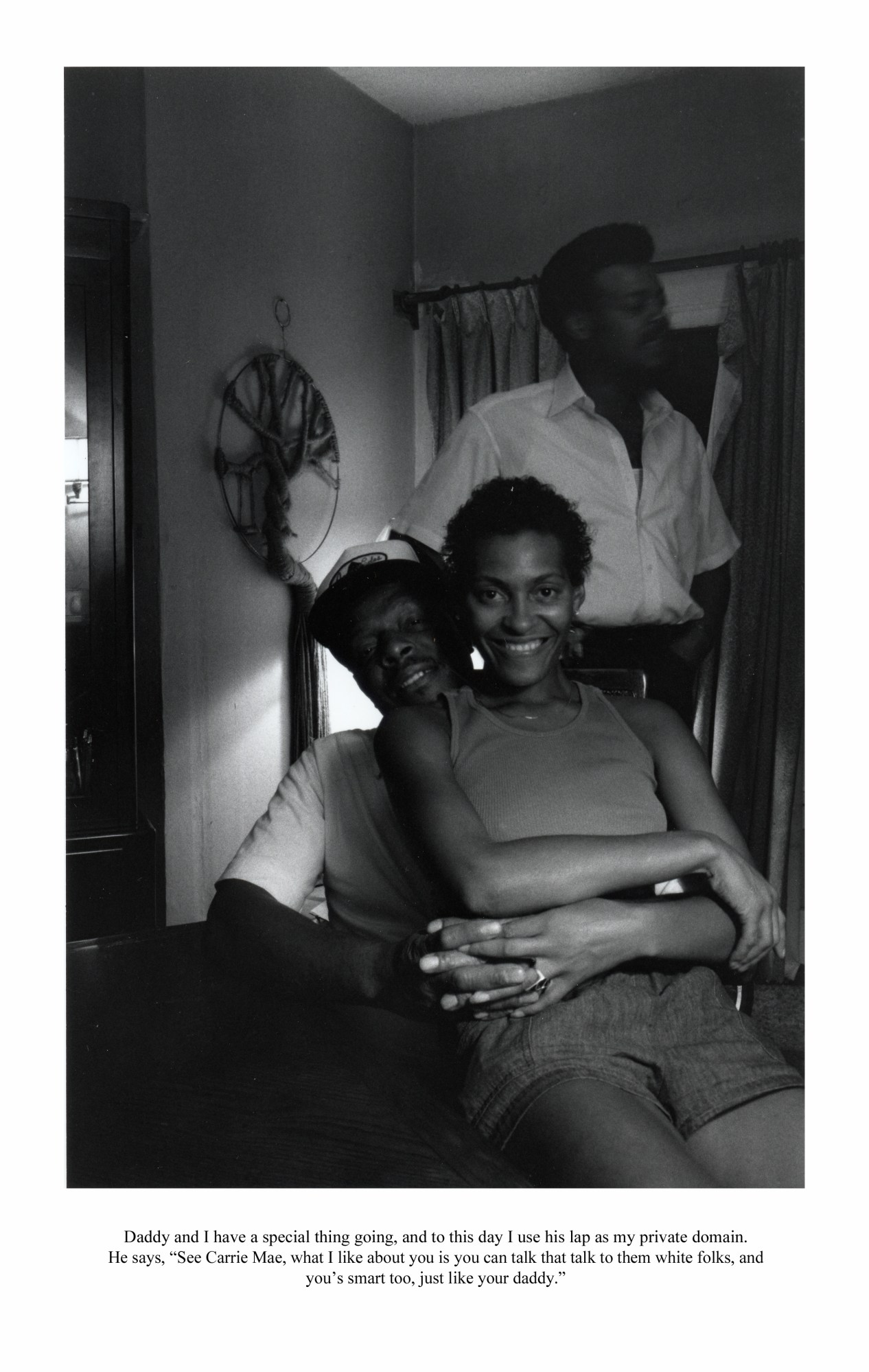

Perhaps that promise grew from a seed nurtured early on. Growing up in Portland, Oregon, Carrie was born the second of seven siblings in a close-knit family. Her mother and father had migrated from another life as sharecroppers in Mississippi, and both gave their children full permission to find themselves authentically. “I owe a great debt to both my mother and my father for their love of me, and their guidance, and for giving me that sense that I had a right to be, a right to be heard, a right to a voice and a right to my opinion. What they gave me as a sort of backbone for understanding how I could be in the world — that who I was in the world was singular.”

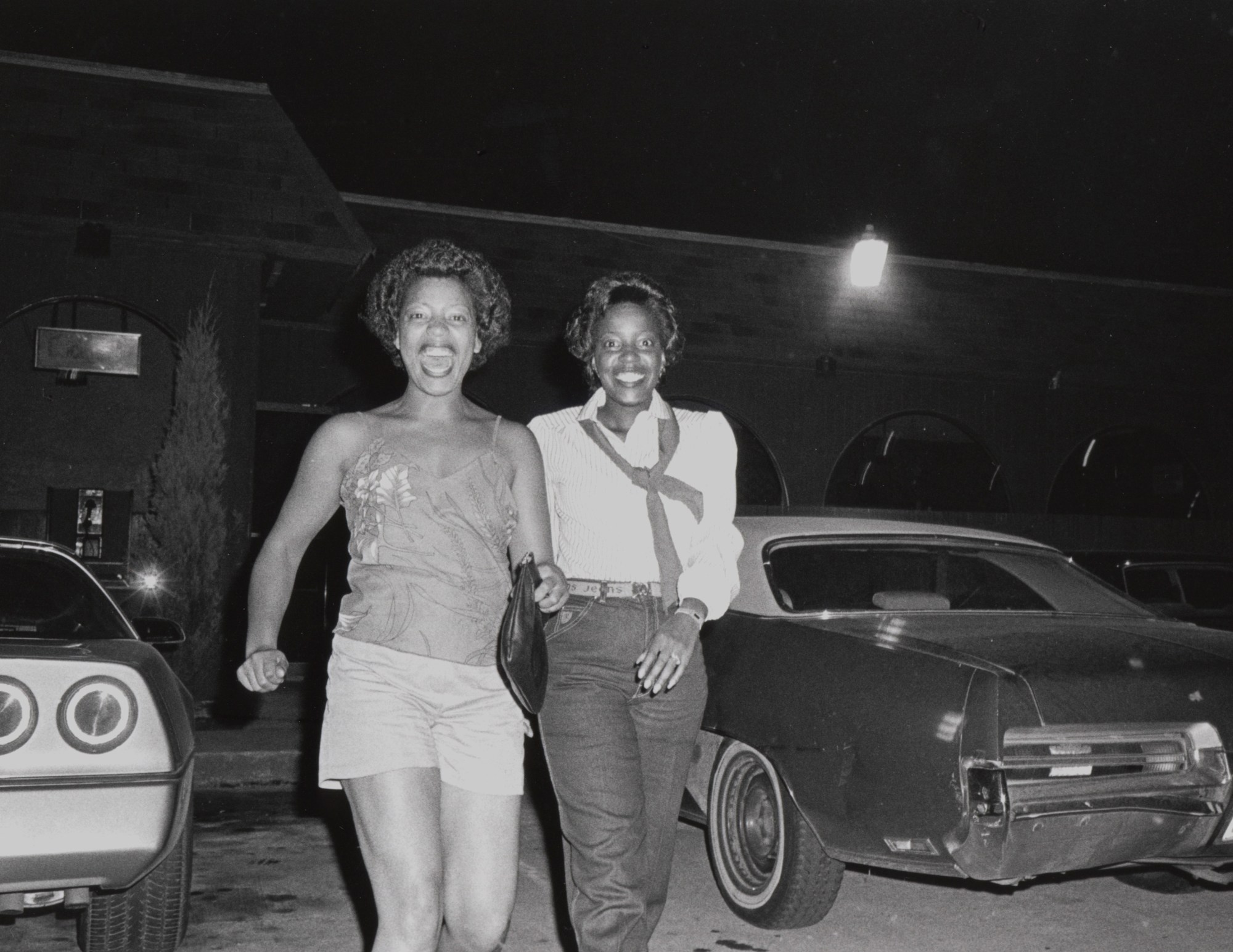

After giving birth to her daughter at 16, Carrie left home in 1970 with her sights set on San Francisco and plans to study modern dance at a workshop led by the choreographer Anna Halprin. As Carrie began experimenting with dance, using her body as a connective tool and performative element, she began taking self-portraits. Legend has it her first camera was a birthday present from an early boyfriend, a Marxist labour organiser she met in the city, with whom she would photograph demonstrations.

By her early 20s, Carrie had moved to New York, inspired by Zora Neale Hurston’s documentation of the Black experience and The Black Photographer’s Annual, which featured work by Roy DeCarava and artists from the Kamoinge Workshop, like Ming Smith. The photographer Dawoud Bey, also a Kamoinge member, would ultimately become one of Carrie’s lifelong friends. She went on to study photography at the Studio Museum in Harlem and began seeing herself as part of an expansive network of creative output. “I started my career really looking at other artists and trying to build a path for other artists that I cared about. That work continues unabated. It is not ceased by any stretch of the imagination.” It is a philosophy she eventually shaped into a practice of curating convenings — bringing together artists, writers, musicians and thought leaders for programming that lives alongside her exhibitions— which has become a cornerstone of her practice. One of the most iconic convenings was curated in alignment with The Shape of Things at the Park Avenue Armory in 2021, which is on view again this year at Luma Arles.

In the late 80s, while teaching as a photography professor at Hampshire College, Carrie and her colleagues were absorbed in Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, the seminal 1973 text laying a framework for the “male gaze”. She noticed her female students resisting their most instinctual impulses in self-portrait work, and the observation became a catalyst for The Kitchen Table Series, a landmark offering chronicling moments in the life of a woman navigating self-actualisation. In creating the series, Carrie made use of a skill she’d developed as a dancer, channeling the feeling of embodiment to access herself.

Upon reflection, she says it’s a tool she continues to use today. “When I step back, when I allow myself to really process what is happening, to smell myself, to feel myself, to know my body, to touch it, to sense it, to be comfortable with it, is when I think I have the greatest revelations about anything. It doesn’t come when I’m at my desk. It really comes when I’m at rest. There’s gotta be this sort of moment where you step away and engage something that’s larger than yourself. The answers, I think, are revealed. Revealed. Because they’re there. They’re just waiting for you to pay attention enough to get out of your own way so that you can actually receive what it is that you have to offer.”

While she might be best known for The Kitchen Table Series, Carrie has achieved a prolific output in a career spanning over four decades, reshaping the art world for generations of artists while exploring themes around gender, identity, race and social justice. She does not consider herself a political artist, but her work deeply investigates the complex contours of Black life. “I am an artist concerned with the political, and how to shape that, how to bring certain kinds of ideas to a public that might engage them in asking certain kinds of questions, pointing towards certain realities to be unpacked, considered, negotiated.”

A lesser-known work, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, is a reproduced collection of daguerreotypes capturing slaves in 1850 commissioned by the Harvard scientist Louis Agassiz. She stained the images red and framed their faces in lens-like circles, subverting the historical use of such images and drawing focus to their humanity, dignity and stolen agency. Harvard threatened to sue Carrie for rescinding a contract promising not to use the photos without permission, to which she responded, “I think that your suing me would be a really good thing. You should. And we should have this conversation in court.” Harvard retreated and ultimately acquired the series for its collection.

The 1997 series Not Manet’s Type troubles the work of artworld masters like Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp, injecting the presence and perspective of a Black female into art historical discourse. Beyond photography, her expansive practice also includes video and multimedia installations, like Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment, a commentary on the human rights movement in the United States she created in collaboration with students from Savannah College of Art and Design, or Afro Chic, a short film playing on the visual aesthetics of the fashion show in order to question traditional standards of beauty.

I ask Carrie if her methodology has changed since she began working. “I probably get up a little later than I used to,” she offers with a laugh. “I used to get up at about five every morning. Now I probably get up at 6:30. But the practice really is fairly consistent. It’s like being, you know, a musician. A pianist. Every day you get up, and you go to your instrument, and you work. You work through the difficulties, you work through the problems, you work through the joy, and you are always surprised when the magic comes. It all begins to flow, and it makes sense.”

Her approach may not have radically changed, but so much about the world — and photography itself — certainly has. Still, she feels her hard-won wisdom continues to ring true, even through the emergence of technological innovations like AI that complicate the relationship between artist and artwork.

Carrie looks optimistically into the distant future. “I find it all thrilling and exciting, and I hope to be around to watch it for a long time as it unfolds. I know we are on the cusp of something, but we are a long ways off.” She notices that when the digital camera was first introduced, the prevailing narrative was that it would change everything. “It didn’t,” she says. “We have a gazillion more photographs in the world, but it hasn’t really changed essentially what we do or how we do it. I think the same thing in part is true about these new technologies. We are in the now, and as much as we attempt to imagine the future, it’s almost an impossibility.”

“It raises fascinating questions, but the only way to get to those possibilities is to really start with now. In order to change the future, you have to start with where you are and understand really where you’re placed on this path, in this universe of ours.”

Credits

© Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.