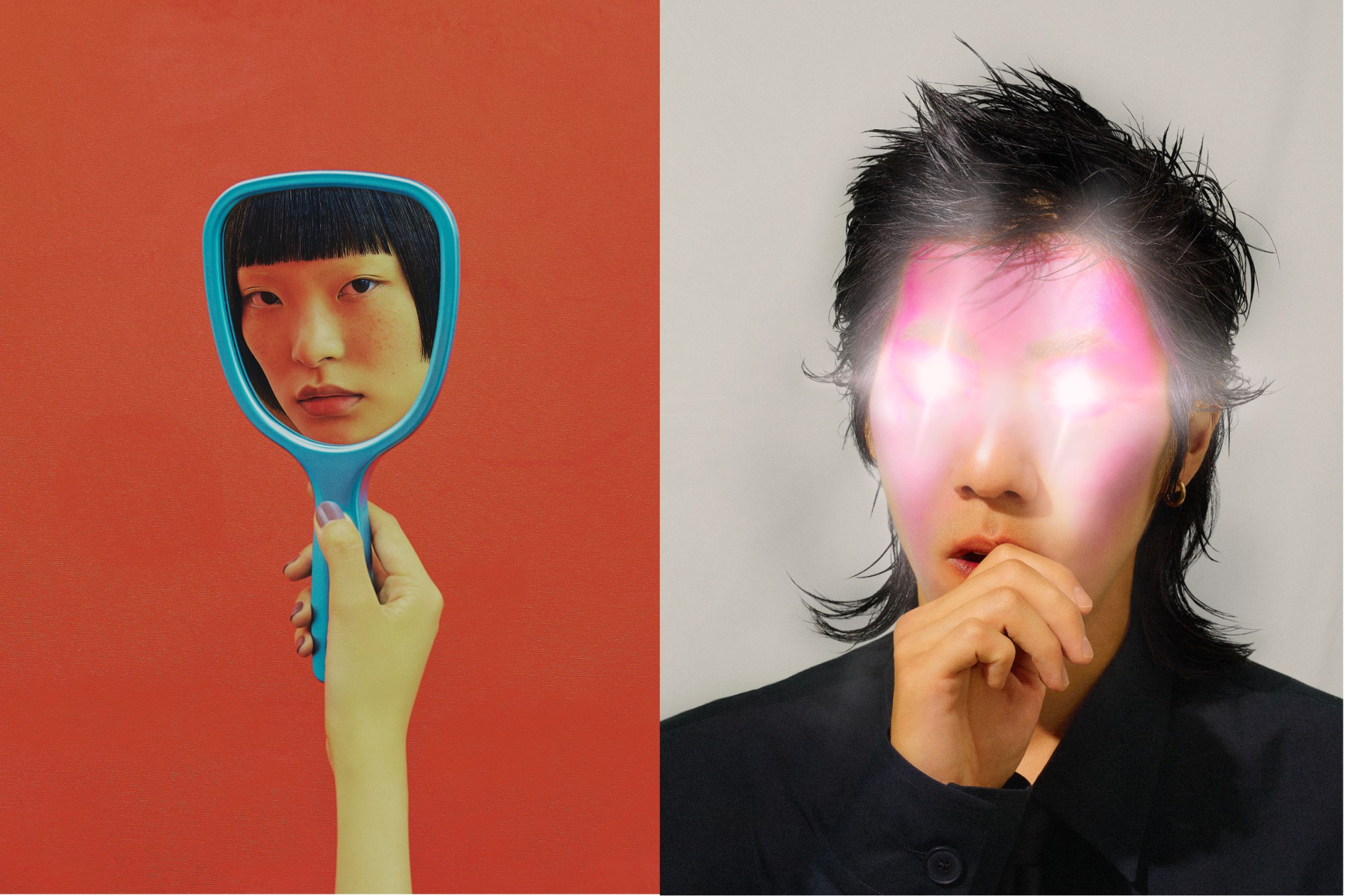

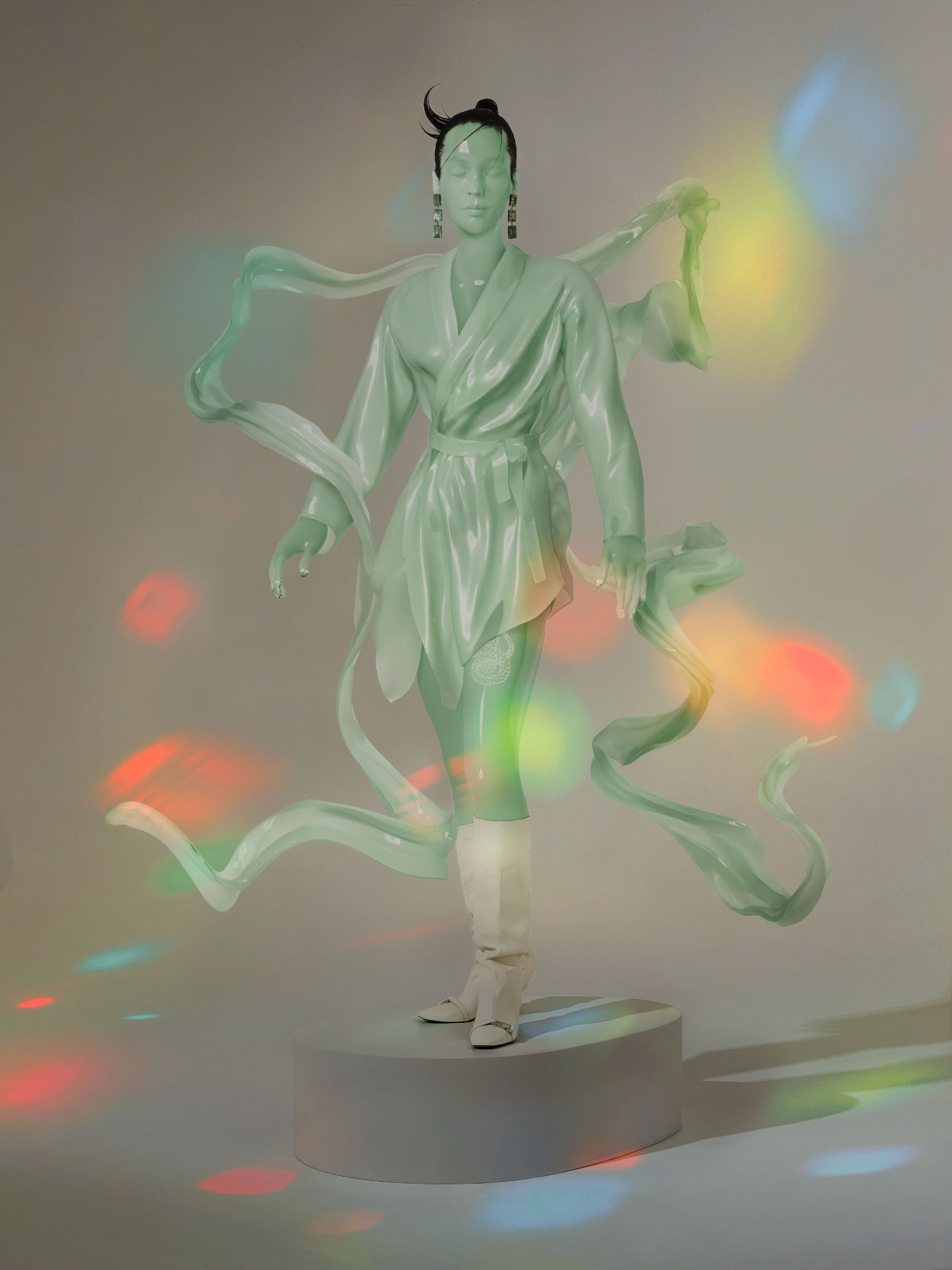

In “Hug of a Swan,” French-Vietnamese photographer Nhu Xuan Hua pivoted from her roster of fashion clients (Maison Margiela, Dior, Kenzo) and magazine commissions (like a BTS cover for TIME) to create her first museum showcase, recently on view at Huis Marseille in Amsterdam. Her first publication, Tropism: Consequences of a Displaced Memory was released in September by Area Books when her exhibition opened. The show featured archival photos of her family, digitally manipulated to disorienting effect: relatives are rendered faceless apparitions, their void-like silhouettes highlighting the intangibility of the past and the phantom quality of heritage, even one’s own. The images, displayed throughout four rooms, turned into immersive installations that conjured grand temples and family gatherings celebrating the strength of Asian women.

Speaking at a café in Paris’s 10th arrondissement, Nhu Xuan discussed diasporic investigation, 80s Vietnamese music, and an unexpected thrill at border control.

Tell me about your trajectory to becoming a photographer.

Both of my parents are Vietnamese. I was born in France, I studied in France, but I feel like I grew up in London, where I moved in 2012. Over time, I’ve come to understand it’s not a necessity to feel rooted, and maybe it’s richer to grow in different places. I grew up in the suburbs; I was the only Asian person in my middle school. You reject your culture because you know people love reminding you that you’re different, so you want to fit in. The way to fit in is to see yourself as a white person.

This is the thing in France: people teach you to forget about where you come from. That’s why I say I feel like I grew up in London, because it opened so much up to me. London is where I discovered that community means unity: it’s easier to break a wall with a group of people, rather than on your own.

I did a two-year school, because I needed a technical foundation. I wanted to practice straightaway and create something with different creative minds — and I needed to prove to my parents that I could make a living out of it. I’d told myself, I’m gonna become a photographer at 25. Maybe a week before my 25th birthday, I got my first job: a lookbook for a brand, a very small thing, but I was super happy that, you know, I managed to tick that box.

There are several notable cultural references in your work. How did these shape your thinking?

I started my personal project, Tropism: Consequences of a Displaced Memory, which is based on pictures of my family. It’s named after [Russian-born French author] Nathalie Sarraute’s book Tropisms, in which she’s studying inner consciousness and how it brings back moments from the past. Right now, I’m reading this book by Trinh T. Minh-ha, a Vietnamese author who wrote Woman Native Other. It’s about post-colonialism and feminism. In the last chapter, she speaks about the relationship between women and words; it’s called ‘grandma stories.’ My own grandmother passed away the day after my exhibition opened. I was thinking about all her stories that I’ve never heard; I didn’t grow up in a house where a grandmother tells you those.

In addition to seeking out family stories, what did your research entail?My family was split in different places. I started with my parents; then I went to Vietnam for the first time as an adult, in 2016. As soon as I arrived, there was this very inexplicable feeling of connection: the heat when I came off the plane, the smell. When I went through border control, the guy took my passport and said my name exactly the way it should be pronounced. It meant so much to me.

I wanted to reconnect the dots: I was thinking about the rest of my family, and maybe future generations. There’s this fear of disappearance, that the story will not be transmitted. I wanted to reunite everything. Part of me was like, maybe this is material for a future creative piece. But I just knew I needed to do it. And then I had this opportunity for a residency. I’d just come back from Vietnam, so I was like: I’m gonna study the displacement of memories. That’s how the project was born.

How did you figure out an aesthetic for your research?

Growing up, everything had to be perfect. Cultivating this sense of excellence was essential in my family. My parents were always pushing: you need to give your best — you need to be the best. It wasn’t like, what you do is enough. Because they put in everything they had for me, there was this thing of I need to pay them back with good grades. I wasn’t bad at school, but I was not as smart as my parents wanted me to be.

I’ve always loved studying and receiving information from people. So for me, every fashion commission was an opportunity to learn something. I would pick a theme, then read books, read articles, do image research at libraries, from films. Very rarely from other fashion stories or magazines. My mood boards are always, like, 20 pages long; like a dissertation. It was my way to go back to school.

Could you talk about expanding on the photographic component to make theatrical installations as well?

With the installations, I like the idea of having conversations to exchange, share, transmit stories. Each of the four rooms had a soundtrack of Vietnamese music: Vincent Yuen Ruiz’s “Sewing Bodies”; Ngọc Lan & Kiều Nga and Anh Thì Không’s “(Toi jamais)”; Ngọc Lan ft. Trung Hành & Kiều Nga’s “Liên Khúc Tình Yêu (Besame Mucho)”. During the diaspora, existing songs would be translated: musicians would sing part of the song in the original language, and then the other part in Vietnamese. I found it funny and kitschy, but in a very good way, you know? You could listen to this music and isolate yourself in the worlds that are created; you can just lock yourself in with headphones.

Was anything created specifically for the exhibition?

Everything was existing — between 2016 and now — and each room has its own atmosphere, with a color: jade green, sky blue. One was about motherhood and birthdays, very much connected to the idea of celebration. One room was the Temple Room; very Baroque, and connected to Kubrick films, the way he was composing his sets in 2001 or The Shining. The music that I chose for that room was a recording from a theme park in Singapore called Haw Par Villa. It has lots of very absurd scenery, like men being attacked by animals with their arms getting pulled off, or a couple with animal heads, and the rooster-man is slapping the dog-girl — it’s very, very strange, but I loved it. It’s a theme park meant for kids, but it’s clearly not for kids.

In terms of representation, do you feel the culture evolving? Or is the change superficial?

I recently saw Everything Everywhere All At Once: it’s amazing seeing more Asian representation. I have this one memory of the day I went to see Mulan at the cinema, and that was the only time I saw an Asian character in an animated movie. I am so happy that, today, kids don’t have to wait so long to see themselves onscreen.

But one reason why I left Paris was because I felt so underrepresented. In my childhood, I needed to silence so many things; I’m trying to get this confidence of being able to speak up for myself. I think the way I respond is through my work.

Even today, I find it hard to respond to racism on the spot. On my way here, on my bike, I passed by this guy who yelled at me: “Eh, la Chinoise!” Every time it happens, I bite my tongue. Like, I don’t have time to respond to your stupidity. But then, you know, I was upset. I almost wanted to go back and talk to him. But what do I say to this guy? “I’m not fucking Chinese”: it’s too long to explain. People tell me it’s better to ignore, because you don’t have time to educate people. On the other hand, how do I bring change?

Part of the issue is: where do you put energy?

Once, I was doing my grocery shopping and this white French lady came up to me and was like, I was just wondering: how do you make Cantonese rice? I didn’t know what to do; I was so shocked. Then she asked me What herbs do you put in Cantonese rice? And I said We don’t put any herbs in Cantonese rice and I left — I couldn’t even do my shopping anymore. I was angry and wanted to tell her it was inappropriate to assume that because I’m Asian, I know how to make Cantonese rice! But obviously she came to me thinking she had good intentions. She thought she was doing something smart!

That is horrifying.

Some days, I’m allowed to not want to explain, you know?

It’s so casual from the other person — and you can’t bring someone up to speed quickly if they have gone through life with…

No tools.

No tools! You can’t provide them with tools.

I was like, I can’t let this trigger me for too long. The thing is, I’m like: I should have said this…. Oh, I should have said that. The amount of time I thought about the sentence!

You know, I’m making the work to try to show that we actually exist. Other people, until they see us, they’re going to carry on shouting out this kind of stupidity. I guess my way to respond is by creating these moments so we can be more visible to the people who ignore our existence. I’m trying to put all the anger to the side, and just see how we can bring positive change to our discourses.

Credits

Images courtesy of the artist and Huis Marseille, Museum of Photography.